X. THE KHMER TEMPLE MOUNTAIN IN TRANSITION: Koh Ker, Pre Rup, Ta Keo

Koh Ker (928-944)

PRASAT THOM, KOH KER (928-944)

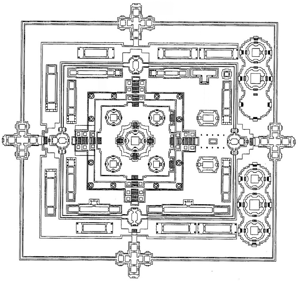

SITE PLAN: PRE RUP (962)

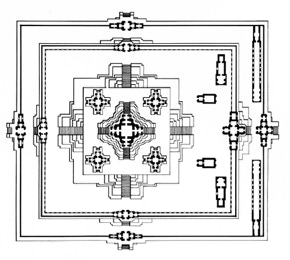

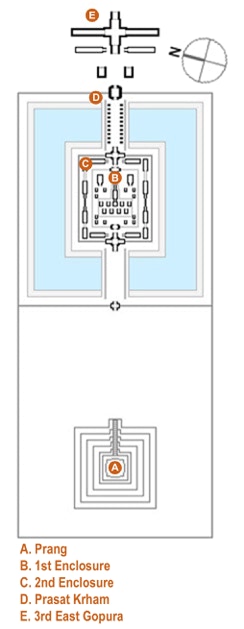

Phnom Bakheng has many more individual elements than the Bakong; though they are more coherently organized, it shows a fissiparous tendency of splintering into peripheral shrines whose gradual reunification in a single monument would make Angkorian temples of the classical period the largest ecclesiastical structures ever built. This consolidation can be cursorily summarized through three successive “temple mountains” from the 10th and 11th Centuries – Prasat Thom at Koh Ker (928-944,) as well as, Pre Rup (962) and Ta Keo (c.1000,) both at Angkor. Of these, Koh Ker is the outlier and not just because it is located 80 km northeast of Siem Reap at Lingapura, the remote bastion to which Jayavarman IV relocated the capital after a long and bitter succession struggle between 923 and 928, when the Khmer empire had two rival kings. Prasat Thom, the “big temple” or “big palace,” aspires to the gigantic (or megalomaniacal) in every respect – from its extensive site plan to its brobdingnagian sculpture. The temple stretches along an unprecedented 800m “processional path” consisting of “palaces” for visiting notables, reception halls (E,) an exceptionally large outer or 3rd east gopura, Prasat Kraham (D,) a wide moat crossed by a colonnaded causeway to a 2nd enclosure (C,) on an artificial island containing a 1st enclosure (B,) with not one or five but nine large and twelve smaller Shiva shrines, (significantly, the patron of the devaraja cult.) This “liturgical axis,” instead of terminating there, continues, recrossing the moat, before entering a second large enclosure with an immense seven-tiered temple mountain (A,) topped by a 5m tall Shiva linga, a less than subtle reminder of its ruler’s potency, but also, perhaps, his dubious legitimacy. This prang rising 35m above the plain is the only Khmer temple mountain with more than five levels and the one most resembling the megalithic, stepped pyramids of Mesoamerica. At Prasat Thom, the structures which are scattered around the compounds of the Bakong and other temples which followed it, are lined up in a carefully-staged, scenographic sequence leading to its ithyphallic climax. Koh Ker takes “linear” or “additive expansion” to one of its logical extremes where each aedicule or element becomes a free-standing unit of a protracted “liturgical chain” – the paratactic opposite to the hypotactic or syntactic compression of the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple. This same solution would be applied at narrow Khmer mountain sites, such as Preah Vihear and Phnom Rung, where there was no room to integrate peripheral shrines or “aedicules” into concentric terraces, galleries or enclosures. The clutter of small, individual shrines in Koh Ker’s island 1st enclosure reflects a deliberate displacement of the normal focus from the central shrine, which becomes just an anti- or ante-climax, next to Jayavarman IV’s unmistakable, unprecedented prang and linga as the primary focus of worship, however over-emphatic.

Ta Keo (c. 1000)

VIEW FROM THE EAST OF THE 2nd - 5th TERRACES, PRE RUP (962)

A. Prang

B. 1st Enclosure

C. 2nd Enclosure

D. Prasat Kraham

E. 3rd East Gopura

SITE PLAN: KOH KER (928-944)

Pre Rup (962)

Jayavarman IV’s son, Hashavarman II’s contested reign lasted less than three years and ended with his erasure from the historic record. When Rajendravarman (944-968) assumed the throne, he returned the capital to Angkor to stress his continuity with the pre-Koh Ker past. His own “temple mountain,” Pre Rup (962,) pointedly returned to the precedent of Phnom Bakheng with its five-level pyramid and quincunx of shrines on its upper terrace. At the same time, it prefigured features which would characterize the “temple mountains” of the classical era. For example, Pre Rup’s 3rd and 2nd enclosures, (which are usually also counted as its 1st and 2nd terraces,) are almost completely lined with the narrow, rectangular buildings whose function remains a mystery, which were already present at the Bakong and would be consolidated into a continuous gallery at the next, state temple, Ta Keo (c.1000.) They and the two west-facing “libraries” of Pre Rup’s 2nd terrace would become standard features of future Angkorian temple mountains – the Baphuon, Angkor Wat and the Bayon. Between them is the plinth, long-mistaken as a platform for funeral pyres and responsible for the temple’s rather gruesome modern name which means, “Turning the Body.” This was, in fact, a Nandi shrine for Shiva's vehicle, a bull, a common feature in Saivite temples from Preah Ko to Prambanan to Halebidu, (but not adopted in later Khmer practice.) Squeezed between the 1st and 2nd enclosures are five of an intended six large towers with no apparent relation to the rest of the temple, as if waiting to be set around the pyramid, as they were at the Bakong and at the corners of Angkor Wat’s 2nd and 3rd galleries, though far too big for Pre Rup’s narrow terraces.

Pre Rup’s pyramid is off-set to the west of its broad 2nd terrace (1st or inner enclosure) and rises abruptly in three terraces subdivided by two intermediate tiers, in effect, a five level pyramid like Phnom Bakheng. This combination of three terraces subdivided into five tiers recurs at Ta Keo and the Baphuon; (Angkor Wat and the Bayon have only three terraces.) The central tower of the panchayatana or quincunx on the 5th terrace is raised above the other four on a plinth with two tiers or sets of moldings, uniting it with the banding of the five tiers below to form a single vertical flow, accentuated by the unbroken flight of steps from the 2nd to 5th terraces, an effect achieved more deliberately at Ta Keo (c.1000.) The distance from the central tower to the north, south and west 1st and 2nd gopuras is equal, so the western side of the temple forms two symmetrical squares or half a square mandala. The distance to the 2nd east gopura is 25% longer than to its western counterpart for a net 12.5% westward off-set. The 3rd terrace has twelve shrines, as on the Bakong’s 5th, but here they are placed, like the quincunx of towers above them, symmetrically around the pyramid which is also square with no westward offset.

EAST FACE, TA KEO, (c.1000)

The development from Pre Rup (961) to the next temple mountain, Ta Keo (c.1000,) is direct and leads logically to its classical expression at the Baphuon (1061) and then Angkor Wat (1113-1150.) With Phimeanakas, the three-tier private temple pyramid in the royal enclosure, and the North and South Khleangs across the ceremonial way from it at Angkor Thom, Ta Keo exemplifies the poorly documented, hieratic Khleang style which briefly flourished between the narrative Banteay Srei (968) and naturalistic Baphuon (1061) bas reliefs. Ta Keo is thought to have been the state temple of Rajendravarman’s son, Jayavarman V (968 - c.1000,) though it was clearly left infinito, presumably because of that monarch’s death and the period of disputed succession following it (1002 - 1010;) since it was never dedicated, it lacks the inscription which might be able to answer the question of its origins. At the temple, unfinished blocks of sandstone have been hoisted into place awaiting sculptural embellishment, suggesting Khmer sculpture was done in situ not in workshops. Ta Keo was the first state temple to be built entirely of sandstone without any laterite or brick. The precision of its refined but austere detailing, squared fillets (pattika moldings,) cornices and pilasters, has won it the modern sobriquet, the “Crystal Temple,” though its actual name like so much else about Ta Keo remains unknown.

As at Pre Rup the broad 1st and 2nd terraces provide a base for three, concentric, square, upper terraces, which form a single pyramid equidistant from the 1st north, west and south gopuras but offset 12.5% to the west. The three terraces rise at a 70° angle, one of the steepest inclines at Angkor, to a panchayatana of shrines on the 5th terrace. To an even greater extent than at Pre Rup, the central tower continues the vertical momentum, rising above the terraces and the four other shrines on a heavily redented pedestal with five discrete tiers, like the pyramid on which it rests, occupying fully 60% of the upper terrace. It is so imposing it pushes the four peripheral towers to the edges of the terrace, so that together the quincunx resembles a single mountain with four ridges; (a very loose comparison might be made with a Nagara or Northern Indian shikhara with four urushringas.) The central tower’s four, long staircases are brought so close to the pyramid’s unbroken three-tiers of steps, they almost seem one continuous flight.

For the first time at Angkor, the barely-emerged, faux-porches of the original Khmer shrine or prasat “aedicule,” from Sambor Prei Kuk to Pre Rup, emerge half-way, (i.e., half their width,) from Ta Keo’s towers, while a second smaller porch or vestibule, also half its width, with jambs, lintels and pediment, is attached to the first, so the overall outline of the shrine becomes a Greek Cross with tapering arms or a square cella with two superimposed crosses, therefore, pancharatha. The sides of these porches are fenestrated with windows so large their frames seem more like columns with lintels than mural.

The clutter of twenty-eight buildings in the 1st and 2nd enclosures of Pre Rup and the twenty-one at the Bakong has at Ta Keo been reduced to six – two parallel, narrow structures against the eastern wall of the 1st (outer) terrace and two smaller ones in the eastern corners of the 2nd plus a pair of “libraries” also on its east. The enclosure wall of this 2nd terrace forms the back of a gallery with large inward-facing windows, reminiscent of a colonnade, which runs continuously along all four sides of the terrace. Since this gallery, unaccountably, lacks any entrances from the terrace, it seems unlikely it was intended as cells for resident monks, a hostel for itinerant pilgrims or a path for parakrama or circumambulation. If it was not intended to be regularly entered or walked through, there is the possibility it might have functioned something like an art gallery, framing still-uncarved bas reliefs like those found at later temple mountains or housing rows of individual shrines like the terraces at Borobudur or Phnom Bakheng. A similar but smaller gallery, accessible but too narrow to be anything but a corridor, lines the inside of the 1st enclosure of the roughly contemporary mountain temple, Preah Vihear (11th Century.) The 2nd or outer enclosure at Banteay Samre, built more than a century later, also has inward-facing windows with no entrance doors. Whatever their purpose, these galleries mark an important advance towards integrating the Khmer temple’s parts by incorporating them in lateral branches projected from the four gopuras, thereby outlining each terrace with a gallery marking each stage of a temple’s “cruciform” (“axial and lateral”) extension. While the gallery at Ta Keo opens to the inside, the walls of outward-facing colonnades, like those at Angkor Wat and the Bayon, are carved with narrative bas relief visible even to those outside their three restricted inner enclosures, forming a barrier or cordon sanitaire around the sacred, by mirroring back the profane world of men, history, battles, myths and heroes outside them.

SITE PLAN, TA KEO, (c.1000)