The Temple in its Terms: Two Asymmetries

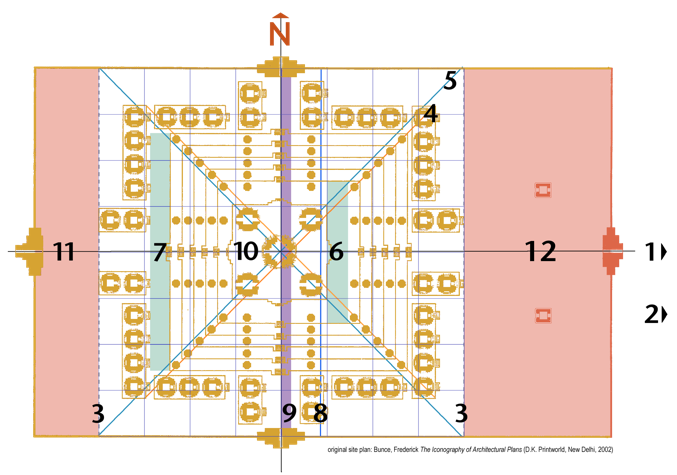

Phnom Bakheng was carved from the rocky summit of its eponymous hill, paring away the five terraces of its pyramid and then leveling the remainder to make its 1st enclosure. A 2nd enclosure surrounded the hill itself with four gopura and a moat. On its east, a path for elephants and an unbroken flight of stairs for hardy pedestrians led from the 2nd (outer) enclosure and present-day highway between Angkor Wat and Angkor Thom up to the 1st (inner) enclosure. Like the Bakong, Phnom Bakheng displays asymmetry along its east-west axis but it has a second asymmetry as well, between the center of the central tower and the center of the stepped pyramid it crowns. The temple’s 1st enclosure is a rectangle, 120m x190m, its length more than 1/3 longer than its width. Within this rectangle, the central tower and hence the north-south axis of the mandala is set-back to the west by the difference between its western and eastern margins (11 and 12, shaded pink) which equals 14.3% of the 1st enclosure’s length. (The Bakong’s 1st enclosure also had a western and eastern strip separating its pyramid and peripheral shrines from the profane world of the “charnel grounds” beyond (see figure 13.) Diagonals drawn through the central shrine to the north and southern enclosure walls (5, blue lines) define the mandala’s east and west “threshold lines” (3, dotted lavender lines) forming a 120m square which can be divided into a 64-pada manduka mandala (lavender grid) which contains and organizes the temple’s 109 shrines and its five terraces. The plinth (10) on which the temple’s quincunx or panchayatana of five towers rests occupies the mandala’s four central Brahma padas, while the twelve devika padas contain the pyramid’s upper three terraces, on the west, and upper two, on the east. This second asymmetry results from positioning the quincunx of towers (and hence the mandala's and the temple’s center) 7m to the west on the pyramid's 5th terrace, equal to 3.6% of the enclosure’s length or, the width of two terraces (shaded green.) This has a number of consequences: 1) the center of the pyramid (4, orange diagonals) and the center of the quincunx of towers and north-south axis (5, blue diagonals) are separated by 1.8% of the enclosure’s length or 3.5 m (the width of 9, the purple bar;) 2) the pyramid or 1st terrace is thus flush with the eastern row of shrines but separated from the western by the width of two terraces (7, shaded green;) 3) the diagonals (4, orange lines) drawn through the pyramid’s midpoint intersect the front corners of the eastern row of shrines but the backs of the western; 4) diagonals drawn through the central tower (5, blue lines) intersect the four corners of the mandala containing all 109 shrines and cut through the rear corners of both the eastern and western rows of peripheral shrines.

The net westward setback of Phnom Bakheng’s 109 shrines by 14.3% might be explained, in part, because it is the point at which the temple’s broad expanse becomes entirely visible to a visitor reaching the top of the staircase from the road below. Today a photographer still has trouble framing the temple’s width from this position – even without showing the entire quincunx of towers, as in the photograph on the previous page. The westward setback of most Khmer temple mountains serves to lengthen the “liturgical axis” both to increase the “spiritual distance” between the shrine and the profane world outside (and here below) and to provide space for rites preparatory to viewing the “awakened god” within his shrine. The reason for the second asymmetry, between the plinth with its quincunx of towers and the pyramid is more difficult to rationalize. One could at least note that the space it opens between the pyramid’s western edge and the eastern-facing steps of the western row of peripheral shrines is necessary to enter them but this result could probably have been attained more directly and without violating the temple’s symmetry. As with the Bakong, another reason might be adduced from the visual experience of the worshipper approaching the shrine along its “liturgical axis,” as with the net westward set-back. The additional 7m set-back of the quincunx of shrines on the 5th terrace increases the distance between the shrines and the eastern, “liturgically privileged” staircase to them so that, at its top, the quincunx of shrines can be seen as an ensemble, which would not be the case if the eastern two towers were closer to that terrace’s edge. The 7m space opened could also provide a prominent space at the culmination of the “processional path” where public rituals would be performed and notables congregate before receiving the darshan of the resident deity, Shiva, venerated within the shrine. This same setback would, at the same time, delay the full view of the shrines to anyone ascending the eastern staircase until they stepped onto the terrace because the terraces at Phnom Bakheng are so much steeper than at the previous temple mountain, the Bakong.* As noted in reference to numerology, the pyramid’s slope affects so many other relationships and is, in turn, determined by so many variable factors, it is impossible to know what motivated this seemingly insignificant but, nonetheless, deliberate asymmetry. Did the temple’s designers care if the quincunx of shrines appeared dramatically or gradually? Did it matter to them if the entire shrine and towers or just a part were visible from the 1st enclosure’s eastern entrance?

While this slight asymmetry might make the towers appear marginally more abruptly or seem a little more distant and celestial, it is certain, and surely more significant, that the incline of the pyramid parallels and hence extends the slope of the hill so that architecture and topography are rhymed as two tiers of a single temple mountain. The appropriation of landscape to serve a larger symbolic objective also incorporated the surrounding “city on a plain,” Yasodharapura, in a cosmological geography, transforming secular terrain into a sacred landscape where hill and temple, aedicule and ideal, merged. Mt. Meru’s summit and Phnom Bakheng’s upper terrace became the place where the god, Shiva, entered his two earthly avatars, the devaraja linga and, perhaps, the Khmer king. Thus, the city received the deity’s darshan whenever it looked up at the temple, knowing the god was there, though his image might be occluded or mediated by the visage of the monarch. Two centuries later, traffic passing on the road below Phnom Bakheng, soldiers and elephants, nobles and peasants, oxcarts and palanquins, on their way to Angkor Thom, would again become actors in a symbolic, architectural drama. As they crossed the bridge over the moat to the city’s south gate, between two rows of asuras, demons, and devas, gods, twisting the naga, Vasuki, its balustrades, they would re-enact the Khmer creation myth, “The Churning of the Ocean of Milk,” the Samudra Manthan, to extract amrita, the elixir of immortality. Just as the demons had been promised a drop in return for their participation,but in the end only the gods got to sip, one might observe – no doubt, tendentiously – that the quotidian business of the Khmer Empire ultimately served only the monarch’s pretensions of a posthumous divinity, as the monuments of Angkor testify so eloquently.

*The slope of the pyramid can be calculated by dividing half the difference between the widths of 1st and 5th terraces ( 76 - 47/2 = 14.5m ) by their height (five times the height of a terrace or 2.6m x 5 = 13m, then adding the height of the shrine’s plinth (1.6m) resulting in a height of 14.6m and a ratio of width to height of 14.5/14.6, roughly a slope of 45°. Since the distance of the central tower to the edge of the 5th terrace equals half that terrace’s width plus half its eastward offset (9, the purple bar in figure 15) or 23.5m + 3.5m = 27m, the central tower would need to have been 27m high before its peak became visible from the foot of the eastern steps. At the level of the 4th terrace, (10.4m off the ground and the last point where the pyramid’s slope would restrict sight lines to 45°) the top of a tower 16.6m tall (including its plinth) would become visible; (in the absence of the 3.5m westward offset, a 16.6m tower’s top would become visible from the stairs between the 2nd and 3rd terraces.) In any event, the central tower of Phnom Bakheng, would have appeared marginally later as a result of the 7% westward remove.

TWO OF THE TWELVE SMALL SHRINES ON THE 5TH TERRACE, PHNOM BAKHENG (907)

FIGURE 15: ANALYSIS OF SITE PLAN, PHNOM BAKHENG (907)

1 Stairway from the foot of the hill to the 1st enclosure

2 Elephant Path from the highway between Angkor Wat and

Angkor Thom to the 1st enclosure

3 East and west “threshold lines” of a manduka mandala

4 Diagonals drawn through the midpoint of the pyramid

5 Diagonals drawn through the central tower (north-south axis)

6 Westward set-back of the central tower and quincunx of

shrines on the 5th terrace (shaded green)

7 Corresponding westward set-back of the western row of

peripheral shrines (shaded green)

8 Line marking the midpoint of the 1st enclosure’s length

9 Difference between the midpoints of the mandala, central

shrine and north-south axis and the pyramid (shaded purple)

10 Plinth with quincunx of 5 tower shrines

11 Western margin between the 109 shrines and the western

enclosure wall (shaded pink)

12 Eastern margin between the 109 shrines and the eastern

enclosure wall (also shaded pink)