ANGKOR THOM (c.1000 - 1431)

ELEPHANT TERRACE, ANGKOR THOM (TPQ 1181)

ANGKOR THOM (c.1000 - 1431)

ELEPHANT TERRACE, ANGKOR THOM (TPQ 1181)

This catalog has documented most of the major Khmer ecclesiastical monuments both inside the walls of Angkor Thom and beyond. It remains for the present photographic survey to note the few remaining examples of that city's civil architecture. The Khmer employed stone almost exclusively for their religious structures, the reason they have left us such a complete record of their temples. Domestic and civil buildings, even royal palaces, except for their foundations, were made entirely of natural materials – wood, thatch, bamboo, wattle – which have all perished. Hence there is the irony that we see all of Angkor Thom except where its rulers and builders spent their daily lives.

We know remarkably little about the origins of a city some historians believe in its day may have been the largest in the world. This in itself provides an idea of how little importance the Khmer elite may have attached to secular life compared with their “monumental existence” in relation to the gods with whom they seem to have identified more closely, especially over the longue durée. Prior to Angkor Thom (Kh. > Big Angkor or City) Khmer capitals seem to have shifted with each monarch and were centered around their individual state temples and possible posthumous abodes – Mahendraparvata on Mt. Kulen,

Hariharalala at Roluos and Yasodharapura at the foot of Phnom Bakheng. This was not an uncommon practice in the ancient world, especially in the case of a feudal societies which had originally been nomadic clans or hordes of pastoralists, hunters and pillagers, before opting for settled agrarian life. The Japanese built a new capital after each king's death which they felt polluted a site: Heian-kyo or Kyoto (794) was their first permanent capital which it remained, if in name only, until replaced by Edo (Tokyo) in 1869 in the “Meiji Restoration.” When Rajendravarman returned the center of the Khmer empire from Koh Ker to Angkor in 944, he probably ruled initially from what remained of Yasodharapura to signal the restoration of a legitimate dynastic line. There is evidence both he and his son, Jayavarman V (968-1000) planned cities around their "temple mountains," Pre Rup and Ta Keo, but these do not seem to have progressed to actual construction.

ANGKOR THOM TODAY

Angkor Thom may have originated as a stopgap to fill this vacuum. During Jayavarman V's sparsely documented reign, the royal enclosure, its private temple and their support services appear to have shifted to an undeveloped area between Phnom Bakheng and Baksei Chamkrong on the south and Pre Rup and Ta Keo on the east. The succession battle which followed his demise, may have indirectly consolidated Angkor Thom's de facto position. Udayditayavarman I (r.1001-1002) and his successor Jayavirhavarman (r.1002-1110) established their court at Angkor Thom and were probably responsible for parts of the royal enclosure and one or both Khleangs. Their rival and the ultimate victor, Suryavarman I (1002/1010-1050,) possibly a Buddhist whose claim to the throne was indirect at best, built no state temple or much else at Angkor and may have felt safer residing away from a hostile court in his fiefs in the north, using Angkor Thom as an administrative center and nominal capital to provide a facade of legitimacy. His son, Udayadityavarman II (1050-1066,) built his state temple, the Baphuon, south of the royal enclosure, as well as the West Baray to supply what must have been a very substantial population. That temple is set back to the west, parallel with Phimeanakas, the temple in the royal enclosure; its long causeway suggests that the city already had a well-defined north south axis, passing Phnom Bakheng and the cluster of temples north of it, following the line it takes today. Suryavarman II's (1113-1150) immense "city in the form of a temple,” Angkor Wat, may have temporarily depopulated Angkor Thom.

URBAN MYTHOPEIA

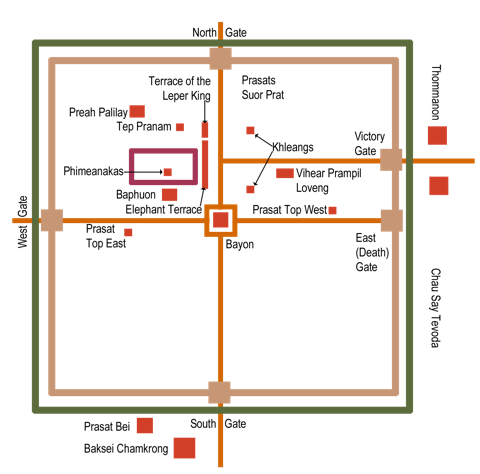

It was Jayavarman's VII who gave the city its present shape in his desire to fortify it against any repetition of its pillaging at the hands of the Cham in 1177 and to give the renewed Khmer Empire a capital worthy of his ambitions. He surrounded Angkor Thom with an 8m high wall and a moat 3km on a side, which like those at Angkor Wat or Prasat Hin Muang Tam, had the usual Khmer associations with Mt. Meru, the four holy rivers of India flowing down its slopes and the seven oceans surrounding its base; the holy mountain itself was represented by the conical Bayon, his state "temple mountain" at its center. These defenses were deemed a Maginot Line so impregnable no attempt was made to strengthen them before the capital's abandonment in 1431, despite its three sacks by the Siamese during the prior century.

SITE PLAN, ANGKOR THOM (TPQ 1181)

SOUTH GATE, ANGKOR THOM (TPQ 1181)

Angkor Thom’s walls were pierced by four gates at its cardinal axes with a fifth, the Victory Gate, adjacent to the city's ceremonial center in the northeast, the Victory Square. The South Gate leading north from Angkor Wat and Phnom Bakheng was the primary entrance to the city; on both its sides, elephants with three trunks pluck lotus blossoms, not just an attractive conceit but a link to the popular myth, "The Churning of the Ocean of Milk." The elephant Airavata, the mount of Indra, king of the Vedic gods, similar to Zeus or Jupiter as "Lord of the Skies," was one of the ratnas or supernatural jewels which congealed on the surface or the sea, along with apsaras and Lakshmi, goddess of prosperity, Vishnu's consort.

The causeway across the moat enacted this central Khmer myth, "The Churning of the Ocean Myth" or Samudra Manthan, in architecture; it was lined on the left with devas and on the right asuras, hoisting naga balustrades, standing for Vishnu’s serpent avatar, Vasuki, Thus Angkor Thom became an exercise in mythopoeia or myth-making, turning the city into a symbol, a literal "urban myth" or, ”a city in the form of a myth” just as Angkor Wat was “a city in the form of a temple.” 1) The moat and city within it were equated with the fecund ocean and the inhabited continents around it. 2) The quotidian work passing over the bridge into and out of the city represented the laborious but fruitful "churning." 3) The Bayon, the state temple at its center occupied the place both of Mt. Meru and Mt. Mandara, the pivot in the myth. 4) The stone head or “face tower” above the gate, personified Vishnu, as chakravartin or “preserver” of dharma on earth, directing the entire effort to insure, if not the amrita of immortality, at least, the empire’s felicity and prosperity. This simile apparently resonated so deeply with the king's conception of his role, he had it repeated on the causeway over the moat before the 4th east gopura of his temple monastery, Preah Khan (1191.)

This has led many to identify the heads directly with that monarch which fails to take into account that Jayavarman VII’s power derived not from his individuality but precisely because he was an emanation of his impersonal Buddha nature, which he associated with the “bodhisattva of compassion,” Avalokitesvara. In a Tantric interpretation, the empire, city and its inhabitants, could be seen as the king’s yidam, the outward visualization of his higher nature, in which his subjects could be regarded as creatures of Jayavarman’s VII’s own subjectivity, “dependently-originated” and hence ultimately illusory. At the same time, his subjectivity and personality were themselves maya, manifestations of a nirguna (apophatic) or niskala (non-manifest) Buddha nature or essence.

“THE CHURNING OF THE OCEAN OF MILK,”

SOUTHERN SECTION, EAST FACE, 1ST EASTERN GALLERY, ANGKOR WAT (1113 - 1150)

DEVA AND ASURA, SOUTH GATE, ANGKOR THOM (TPQ 1181)

On the two sides of the causeway leading across the moat to the South Gate, the devas or gods are on the left and the asuras or demons on the right, both twisting the body of the naga, Vasuki, around the pivot of Mt. Mandara. The gods seem idealized portraits of Khmer nobles, while the demons, given recent history, would probably have been identified with the Cham. They wear the same inverted lotus, flower-pot helmets as in the Bayon's bas reliefs and have the same sub-human, simian visages as the lords of the underworld in the Leper King Terrace. The Cham, who spoke an Austronesian language, related to those presently spoken in Malaysia, the Philippines, Indonesia and Madagascar, were ethnically distinct from the Austroasiatic-speaking Khmer; demonization and dehumanization of the enemy is often cited as a pre-condition for war's brutality.

It is probably tendentious to mention that the asuras were promised a portion of amrita but were denied it when the devas deemed them unworthy of immortality. (Might this have had a counterpart in some agreement between the Khmer opponents of the usurper, Tribhuvanadityavarman, who allied themselves with the Cham, but was later nullified when the Cham refused to leave Khmer territory?) The laborers of Angkor Thom also did not receive an equal portion of the empire's wealth but apparently this parallel never occurred to Jayavarman VII or the city's architects. We cannot know if this irony was also lost on the city's tens of thousands of bonded serfs who built the city and its monuments but remain voiceless.

ROYAL ENCLOSURE, ANGKOR THOM (11TH CENTURY)

This eastern gopura to the royal enclosure leads from the Elephant Terrace overlooking Angkor Thom's ceremonial center, the Victory Square, to the foundations of the royal palace and Phimeanakas, the royal temple to its west, documented earlier in this catalog. The gateway’s modest dimensions probably reflect, not humility, so much as the small number of people permitted to enter or leave the private quarters of the king and his court. Zhou Daguan, the Chinese chronicler who visited Angkor in 1296 -1297 recounts that the king emerged, presumably through this gate, for his public appearances on the Elephant Terrace each day to "show himself" to his subject. His association with the devaraja cult and his deified ancestors may have meant that, like a Hindu god awakened in the garbagriha, his sight (in both senses of the term) bestowed a form of darshan, a shedding of divine blessings on those beholding him. Similar beliefs attached to European monarchs who were endowed with the "king's touch," credited with magical cures. In Mughal India, both Akbar's short-lived Fatehpur Sikri (1571-1585) and Shah Jahan's Red Fort in Delhi (1638 -1639) had Diwan-i-Aam or Halls of Public Audience equipped with special jharokhas or balconies on which the ruler would appear each morning to an expectant multitude of his subjects.

This gopura's pediments and torana arches are more pointed than the hemispheric ones found at the nearby Baphuon (1061) or the rectangular backings at the Bayon (1181-1220.) Its antefixes or acroteria are not convex like those at Angkor Wat and Phimai but standard, square Khmer prasat aedicules with diminishing tiers resulting in a recognizably jagged, stepped pyramid profile. The two aedicular tiers of its shikhara are squatter versions of the portal and cruciform chamber below them. The finial is not an amalaka or kalasa but a shala aedicule, its barrel-vaulted roof parallel with the portal not the enclosure wall, in keeping with its function as a gate. These stylistic details, also found at Preah Vihear and Prasat Hin Muang Tam, argue for a date at the beginning of the 11th Century under Suryavarman I; if so this gopura would be one of the few buildings that king built at Angkor.

The largest of three pools inside the royal enclosure, 25m x 45m x 5m deep, is lined with stone and surrounded by a terrace with steps down to the water. Above the waterline, its sides are carved with marine animals and blithe bathers in a mythical sea which contrasts with the naturalistic Tonle Sap in the "Battle on the Lake" mural at the Bayon. From its less than expert carving, these baths are generally dated to the reign of Jayavarman VIII (1243-1295;) if so, they would be among the last stone structures built at Angkor Thom, as the gopura in the previous photograph may have been among its first.

ROYAL ENCLOSURE, ANGKOR THOM (13TH CENTURY)

VICTORY SQUARE — WHERE IT ALL ENDED

ELEPHANT TERRACE, ANGKOR THOM (13TH CENTURY)

The last stone constructions at Angkor Thom were centered around the Victory Square, the city’s ceremonial center in front of the royal enclosure. Mangalaratha was built to its east and the Preah Pithu group to its north (both treated earlier in this catalog) The most ambitious projects, however, were two contiguous elevated reviewing platforms, the Elephant and Leper King Terraces, extending 300m from the Baphuon’s north enclosure wall to the northern edge of the maidan or parade grounds. They paralleled the main north-south artery or cardo, linking the Bayon to the city’s south and north gates, and further south, Angkor Wat and Phnom Bakheng, and Preah Khan further north. Opposite this esplanade are the twelve

Prasat Suor Prat towers and behind them the North and South Khleangs (c.1000) and the Victory Gate to Ta Keo, an ensemble spanning virtually the entire architectural history of the city. The terraces also marked the eastern limit of the royal enclosure, pictured in the preceding two photographs. Again, according to Zhou Daguan's account, the king, his court and invited guests would gather there where they could survey the monarch’s subjects and marvel at his military forces. They would also share the public spectacles staged in the square which seem to have been more Roman than Greek – martial triumphs, elephant combats, acrobats and wrestlers; no gladiators or Christians are reported. It is ironic, perhaps delusional, that this grandiose prospect was created just in time to witness the Khmer Empire’s rapid and ignominious collapse and survey the vanishing point of Angkor from the historical record.

Five broad staircases lead up from the parade ground to a long terrace faced with pairs of life-size elephants in hunting scenes, not battles. The masonry and reliefs are rather crude compared, for example, with the brick reliefs of Vaishnavite subjects at Prasat Kravan or even the murals on the 1st or outer gallery at the nearby Bayon. A forest landscape is etched behind the elephants without the finesse or delight in naturalistic detail found at other Jayavarman VII's foundations. The target of the hunter's lifted spear is not clear, presumably not his patient mahout or the diminutive woman, (another Khmer pictorial convention.) The elephants are covered in pouncing, probably used to affix stucco or metal plates to the rough-hewn stones, since the pachyderms were likely caparisoned with bejeweled saddles and draped in royal livery.

ANGKOR THOM, ELEPHANT TERRACE (13TH CENTURY)

The projecting central staircase of the terrace is lined with garudas, Vishnu's bird-man mount, and leogryphs, creatures with lion's heads and human bodies, similar to Burmese chinthe, which appear to levitate the platform so the monarch and his guests could look down upon the maidan and the heads of his subjects. They are thus related to the 72 garudas around the 4th enclosure wall of Preah Khan, also a project of Jayavarman VII, where they seem to lift the temple off the profane plane to the divine. Between them are hooded nagas, the ever-present, foes of garudas. The Elephant Terrace takes its place among the serried ranks of mind-numbing processions endemic to the art of militaristic societies which equate rote repetition and discipline with a well-ordered state. It joins Suryavarman's II's grandiose parade along the southwest range of Angkor Wat's 1st gallery and the Khmer armies marching to victory and destruction on the Bayon's 1st eastern one. It is also akin in spirit with early Akkadian mural art which reached a kind of peak (or plateau) under the Assyrians, Neo-Babylonians and Achaemenids, yet, like the rows of serpents at the Temple of Quetzalcoatl at Teotihuacán and the Toltec Atlantes at Tula, the Elephant Terrace is wholly indigenous. Not that the Indic ambit did not contribute its share of monotony, for example, the unvaried sequence of friezes, however imaginatively carved, around the adhisthanas of Hoysala temples, the models for the later depiction of the Desara festival at the Hazara Rara of Vijayanagara (16th Century.)

LEPER KING TERRACE, ANGKOR THOM (13TH CENTURY)

North of the Elephant Terrace is another terrace which provides a glimpse into an unexpected and disturbing side of the Khmer psyche. The Leper King Terrace consists of two redented walls, one 2m inside the other, which project into the Victory Square. The situation appears similar to the "hidden foot" at Borobudur where a wall which had already been carved was covered behind a second deeper one to forestall the terrace's collapse. A narrow, tenebrous trench was dug by the EFEO, so today visitors can see the inner set of murals after 800 years of invisibility.

This trench is very similar to those of the seven registers of bas reliefs on the terrace’s outer walls, confirming the latter as a replacement for the former. Like the Elephant Terrace, these friezes focus obsessively on a repeated theme which has occasioned surprisingly little comment, despite being found nowhere else in Khmer art. Each register consists of cramped galleries filled with figures carved almost in-the-round of seated female attendants with fans or flywhisks (parasols would be superfluous in these tunnels) in attendance on a fierce, central male ruler armed with a sword. The redented corners of the walls feature rearing nagas with up to nine-hoods, confirming that the scene is intended to be chthonic or underground.

The female figures are conventionally referred to as apsaras or devatas which obviates the need for further explanation (or even looking at the carvings.). But comparing the male figures with those on the bridge to the South Gate reveals they much more closely resemble the asuras than the devas, especially those on the original or interior wall. Their bent limbs seem filled with a malevolent energy about to spring at the viewer, as do the lunging multi-headed nagas. The "apsaras" are portrayed, not hovering or dancing, as at the Bayon and Angkor Wat, but crouched beside their lords fanning them like concubines. Their tiaras suggest the nine hoods of the nearby nagas, in keeping with a "metamorphic" tendency often found in Khmer art. They share the lack of individuation characteristic of the Elephant Terrace but present in each of the thousands of apsaras at Angkor Wat. They might be rakshasi, female sorceresses in the Hindu epics, who were assimilated as the "daughters of Mara" or seductive illusion in Buddhism, seductresses akin to Kundry in Parsifal or Circe in the Odyssey, and other phantoms of the misogynist psyche. They here inhabit cramped underground galleries or burrows, like unintended parodies of the rows of attentive devotees of the Hindu gods in the ashrams of the Bayon's 2nd terrace; the spaces, however, are more claustrophobic and Stygian than even the Hells on the southeast range of the 1st gallery at Angkor Wat.

The Hindu underworld was the home of the asuras and these confined spaces would provide ample motivation for their frequent sallies on the airy heights of Mt. Meru. They might also have some relationship to Tantric Buddhism's "transitional state" between incarnations, specifically the hallucinations of the sidpa bardo where one confronts past karmic defilements. The terrace suggests a sense of taboo, barely controlled libidinous, psychological and social forces threatening to overwhelm dharma, the accepted social order, ranged on the terrace above them, a fear which might be not without justification in a period of imperial decline and the erosion of religious orthodoxy, such as 13th Century Cambodia.

The terrace's present name, the Leper King Terrace, is, like most names at Angkor, apocryphal, an invention of the misunderstanding of later generations. It derives from a statue found on the terrace, probably from a later, sub-Angkorian period, which appears to depict the Hindu god of the underworld, Yama, in a pose found in Javanese art but unlike any at Angkor. The nude figure lacks genitals and was originally covered in lichen which later visitors interpreted as leprosy and associated with a local myth of a Khmer king supposed to have been a leper, although there is no epigraphic evidence for that. The myth seems to have arisen in the late Khmer period; it is portrayed with an uncharacteristic poignancy on the 2nd terrace of the Bayon among the Hindu restorationist murals commissioned by Jayavarman VIII (1243-1295) who is unlikely to have portrayed his nemesis sympathetically, instead of smashing him.

The association of the terrace with death has led some scholars like Georges Coedès to propose that it was used as a funeral pyre for the Khmer kings; if so it is the only such platform found at Angkor for a practice which could only have been introduced in the last days of the Khmer Empire. The "crematoria" at the Bakong, Phnom Krom and Phnom Bok would belie this practice, were their identification not equally conjectural. Surprisingly, there is no evidence for any form of royal burial at Angkor, a preoccupation of dynasts and pyramid builders; this is a greater enigma than the Leper King Terrace.

LEPER KING TERRACE, ANGKOR THOM

(13TH CENTURY)

LEPER KING TERRACE, ANGKOR THOM

(13TH CENTURY)

PRASAT SUOR PRAT, ANGKOR THOM (TAQ 1296)

Twelve small towers or shrines stand forlornly in a row parallel to the Elephant and Leper King Terraces in the middle of Angkor Thom's maidan or Victory Square. The only clue to their purpose is a reference in Zhou Daguan's chronicle, written in 1296-1297, soon after the towers' probable construction. The Chinese envoy reports he was informed they were used for some kind of "trial by ordeal" to determine which participant in a dispute was telling the truth: both parties supposedly were isolated in the towers until one became sick (or went mad,) thereby identifying the liar. Were the Khmer so litigious they required twelve towers? Scholars have dismissed this explanation because it is not mentioned in the epigraphical record, although little about Khmer jurisprudence is; they have suggested instead that Zhou's informants were testing the credulity of a foreigner, that is "pulling his leg."

Nonetheless, confinement in small, dark spaces are way-stations on many mystical paths; medieval anchorites, such as Dame Judith of Norwich, immured themselves for life beside European churches; a Sufi cure prescribed spending 40 days crouched inside a cubicle with no windows; the present Dalai Lama's grandmother is venerated for spending 44 years in a brick cell with no light. One of the most powerful and harrowing techniques of the bhavana, development or cultivation, phase of Tibetan Vajrayana, is the mum mishame or "dark retreat," in which the adept spends days or weeks in utter darkness. Could Zhou's rumor have been a garbled version of some occult Tantric ritual adopted into Khmer religion, even though the reigning monarch was a Hindu zealot?

An alternative explanation for the prasats is that ropes were strung between them for high-wire acts; this too seems far-fetched, if only for its triviality. There might be some significance ito the fact that the towers are west-facing – like Temples T and U immediately to their north and Angkor Wat some distance to their south. Thus, they deliberately faced the Elephant Terrace and Angkor Thom's north-south axis but the purpose remains as opaque as the function of the Khmer’s similar west-facing “libraries.” We cannot even be sure that Angkor Wat’s occidental orientation is because of its association with death. As their modern name recognizes, the prasats are loosely based on the shrine prototype or module employed by the Khmer since Sambor Prei Kuk in the 7th Century; early Khmer temples also often consisted of rows of shrines, though not twelve and usually on a shared plinth, for example, the six at Preah Ko (879.) This might seem to provide a possible explanation for their use except there is no indication that they were dedicated to any deity.

One thing about the towers is certain: like the nearby prasat, Mangalaratha (1295,) believed to be the last stone structure built at Angkor, they testify to the rapid decline in Khmer masonry and architectural traditions in less than a century. As their name indicates they seem intended to copy the standard model of the Khmer prasat but they do so without fidelity or understanding. They are not built of brick or sandstone but crudely finished laterite blocks and are rectangular, lacking the subtle pancharathas of the classic shrine. Their front porches lack pilasters; the door frames and lintels are simply squeezed between their walls on which the pediments also rest. The other three sides of the shrines lack porches but their blind doors are outlined with a brick course above which a pediment may have been placed. After this half-hearted start, the builders seem to have been able to manage only two of the canonical, three or four aedicular stories. Since the shrine and these two talas are rectangular rather than square, the towers do not form a step pyramid crowned by a round amalaka and kalasa; instead, they are covered with a shala, horseshoe roof whose gable ends act as second pediments behind the upper story’s notional "aedicular” porch and pediment; shalas were used for galleries and gopuras but never Khmer shrines.

PRASAT SUOR PRAT FROM TEMPLE T, ANGKOR THOM (TAQ 1296)

Like the photograph above of the northernmost Prasat Suor Prat, taken from the naga causeway of Preah Pithu's Temple T (at left,) Angkor has left us abundant evidence of its rise, greatness and fall but the reasons for it have become overgrown with time. Perhaps It is appropriate to end a survey of Khmer architecture with this barely recognizable shrine dissolving in the swamps, forests and sunlight from which this civilization emerged more than 1500 years ago.

78