PHIMEANAKAS (c.1000)

EAST FACE, PHIMEANAKAS (c.1000)

PHIMEANAKAS (c.1000)

EAST FACE, PHIMEANAKAS (c.1000)

It isn't clear when the royal center moved northwest from Yasodharapura, Yashovarman I's (889-915) capital centered between Phnom Bakheng and the East Baray, to what was to prove its permanent location at Angkor Thom – the end of the reign of Rajendravarman provides a TPQ of 968 while the beginning of that of Udayadityavarman II a TAQ of 1050. The unaccountable lack of building activity at Angkor during the long reigns of the two succeeding monarchs, Jayavaraman V (968-c.1000) and Suryavarman I (1002-1049,) divided by the period of contested sovereignty (1002-1010,) leaves a lacuna in the epigraphic record. Also civil architecture, even royal palaces, were made of wood, especially perishable in tropical climates. Therefore the only significant remains from this period are the two Khleangs and Phimeanakas, the private temple in the royal enclosure in the city's northwest quadrant fronting the Victory Square and some distance to the west of Ta Keo. The three monuments have been dated to the first part of the 11th Century and attributed to Suryavarman I largely on stylistic grounds, as a fully-executed version of the Khleang-style, probably introduced here.

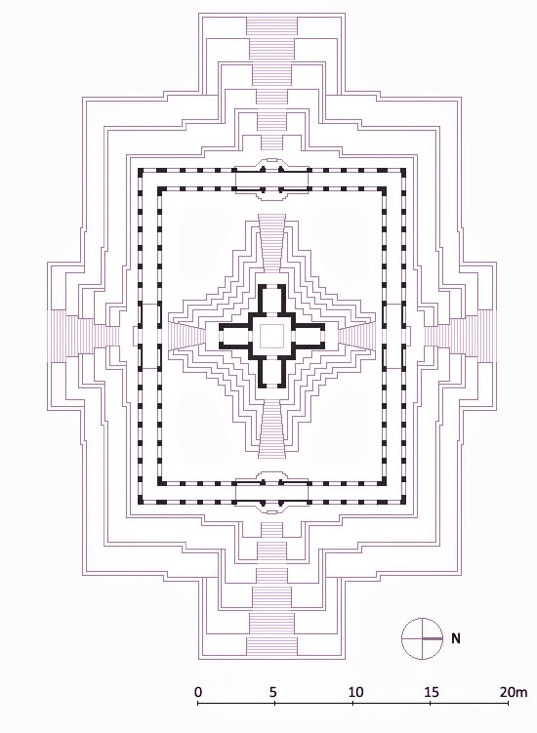

Phimeanakas needed no moat or enclosure wall since those already surrounded the city and royal compound. Nor was it intended as the center of that precinct since it is slightly off-axis from the main entrance and the Victory Gate. The temple is a modest pyramid, 35m x 28m at its base, rising in three steep levels of 12m each, as if the upper three terraces of Pre Rup or Ta Keo had been lifted from their broad 1st and 2nd enclosures. These levels are divided into six tiers by repeated sets of molding, suggested at Ta Keo and a conspicuous feature of the Baphuon. Phimeanakas seems to have set a precedent since future temple mountains – the Baphuon, Angkor Wat and the Bayon – were limited to three terraces. The unbroken flight of steps like those at East Mebon and Pre Rup were originally flanked by three sets of leogryphs and its upper platform surrounded by an open, sandstone colonnade, another innovation adopted at the Baphuon and Angkor Wat. (The Bayon's "podium" is open though crowded with "face towers.")

SITE PLAN, PHIMEANAKAS (c.1000)

There was only one tower at Phimeanakas, a square cella with four porches which unlike the half-emerged ones at Ta Keo were (uniquely) telescoped even further than their width to form rectangles. The tendency, already noted at Ta Keo, for the pedestal to fill the upper terrace was here carried to an extreme; the saptaratha base (the shrine itself is triratha and pyramid pancharatha) was elongated on the east and west, so it reached all four edges of the rectangular platform on which it was centered. It rose in five tiers to a shrine and shikhara which according to the diligent but credulous Chinese emissary and chronicler, Zhou Daguan, in 1297 had a 5m finial of gold, while the Baphuon's equally prominent tower, in deference, was tipped by a copper spire. Of course, this same source reported that if the king did not have intercourse in the shrine each night an the incarnation of a nine-headed naga the empire would collapse. This may have been conflated with the Khmer's own myth of their origin resulting from a similar interspecies mating between Kaudinya, an Indian brahmin, (although, brahmins were strictly forbidden from traveling outside their Gangetic homeland,) who fell in love with Princess Soma, a beautiful nagini or snake goddess, who together gave birth to their race. This has been suggested as additional evidence of the syncretic nature of Khmer religion, combining the Vedic Hinduism of steppe nomads with the indigenous chthonic deities of their own water-logged homeland. No doubt the actual nature of the rites conducted in the royal temple were secret leading to such lubricious and iludicrous speculation; these may have included Tantric sadhanas, as well as, the abhisheka or initiation ceremony into the devaraja cult.

DETAIL OF MOLDINGS, SOUTHEAST CORNER, PHIMEANAKAS (c.1000)

The moldings on Phimeanakas illustrate the austere, cleanly articulated Khleang style. Laterite is difficult to carve with any precision and so the moldings are unrelieved (relieved that is of bas relief or incision.) The original Hindu shapes have been reduced to their simplest outlines with a marked preference for the rectilinear and lapidary over a more flowing cursive. Each of the three tiers is divided in two parts, the courses in the upper half, a mirror image of those below it, emphasizing symmetry over dynamism. The same subdivision of terraces into two tiers recurs at the next temple mountain to be built at Angkor, the nearby Baphuon (1061.)

The sequence of moldings at Phimeanakas is similar to the one at Pre Rup but the courses lack incising, omitting even padmas (lotus petal moldings,) consistent, as noted, both with the sculptural limitations of laterite and the Khleang style’s preference for decorative restraint. They include: 1) a simple base, a rectangular projection from the wall (upapitha/ upana/ bhitta;) 2) an inward-curving, “foot” molding (khumba/ padma/ cyma recta;) 3) an incised fillet (ksudrakampa/ vrttavajana;) 4) a grooved recess (antarita/ kantha;) 5) a narrow fillet (kampa;) 6) a wide recess (gala,) representing a wall (pada/ padam/ jangha) or the space behind it; 7,8) another narrow projection (kampa,) followed by a groove (antarita;) 9) a broad fillet (pattika/ vajana), separating the two halves of the tier and taking the place of a cornice (varandika;) 10,11,12,13,14) a repetition of the sequence (4,5,6,7,8) followed by; 15) a prominent, unadorned fillet (patta/ pattika) defining the middle of the terrace; then 16,17,18,19,20) repeating moldings (4,5,6,7,8) above this central fillet; 21) an incised filet analogous to (3) forming the base for 22) an outward- and upward-turning course (chippika/ adhahpadma/ cyma reversa) which supports; 24) a large, rectangular projection (patta/ pattika) serving as a base for the next terrace or level (bhumi/ tala/ pita) – if regarded as a floor, (prati/ vyalamala,) if as a base (upana/ pitha/ jagati.) A simple Indian wood and thatch minor shrine (alpa vimana) may lurk somewhere in the background of all this – a foundation (jagati,) lower wall (adhisthana,) a railing (vedi,) an open, interior space (gala,) an eave (kapota) and roof or superstructure (vimana/ shikhara,) but at Phimeanakas these structural members have long since turned into repeating, mirror-image patterns, free of representational residue, serving instead the Khmer need to articulate the temple’s repeating tiers.

56