XIV: AN ARCHITECTURE “WITHOUT FORM OR DIMENSION:” The Bayon

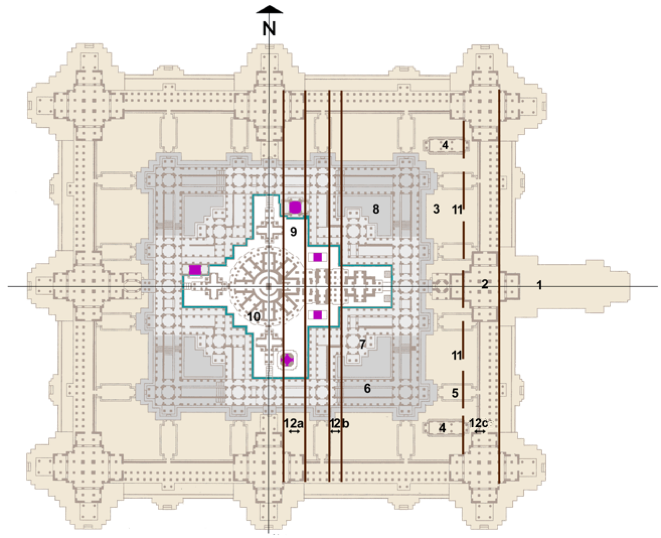

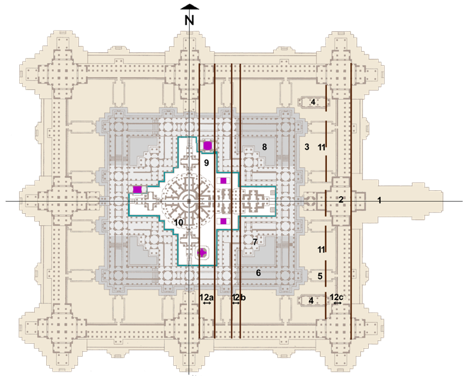

1. Eastern entrance terrace

2. 1st (outer) gallery with Jayavarman VII bas reliefs

3. 1st terrace (3rd construction stage, shaded buff)

4. Libraries (2)

5. Buddhist shrines (16, destroyed)

6. Rectangular 2nd gallery with Hindu bas reliefs (2nd construction

stage, shaded dark gray)

7. Redented (inner) 2nd gallery (1st construction stage, shaded light gray)

8. 2nd terrace (1st and 2nd construction stages, shaded gray)

9. Redented cruciform 3rd terrace, open podium (1st construction

stage, white, outlined in blue)

10. Round sanctuary and shikhara with 8 peripheral shrines

11. 1st terrace “threshold line” (broken line)

12. 12a and 12b = inserts; 12a + 12b = 12c = width of the "threshold line" = 7.3%

westward off-set

"Anomalous" face towers (5)

FIGURE 22: ANALYSIS OF SITE PLAN, BAYON (1181-1220)

The Bayon simultaneously represents both the culmination and the great conundrum of the Khmer “temple mountain.” The one thing of which we can be sure is that it is a monument without precedent or descendant and one of the most powerful statements in ecclesiastic architecture – even though we don’t know what it was stating. Had it had successors, they might make it easier to comprehend the motivations behind its many innovations and stages of construction. The temple clearly engages in a spirited intertextual dialogue with Angkor’s architectural heritage and reflects still obscure theological and political developments during Jayavarman VII’s long reign (1181-1220.) This is suggested by seemingly quixotic changes in direction, not found in earlier Angkorian construction, implying that the temple, like Preah Khan, may not have been entirely planned in advance but evolved or was improvised.

Recent Japanese spectroscopic analysis of the stone used in the temple’s different parts has confirmed what archaeologists long suspected: the Bayon was built in three distinct phases (shaded white, dark gray and buff in figure 22) with additions and deletions subsequent to those. The first stage consisted of assembling an earth and rubble mound to hold a raised, open terrace or platform (9, outlined in blue) in the classic Khmer shape of a redented square with a superimposed cross, hence pancharatha. Because of the usual westward offset, the square was stretched into a rectangle east of the north-south axis. A typical shrine (10) with four porches and shikhara was placed at its center, the axial crossing. A lower, redented, colonnaded gallery (shaded light gray,) without sculptural embellishment but with triple gopuras at its cardinal points, hugged the base of the upper terrace’s podium (platform, plinth, jagati. The second construction phase (shaded dark gray) laterally projected a second, colonnaded gallery (6) from the triple gopuras but at a lower level, forming a rectangular 2nd terrace, in keeping with previous state temple mountains. These double galleries (6, 7) broke the 2nd terrace into a labyrinth of small spaces at different levels in permanent shadow, rendering both circumambulation and continuous narrative murals impractical. The walls of this outer, rectangular colonnade (6) were carved rather crudely with scenes of Hindu rituals, presumably during the brief Hindu restoration under Jayavarman VIII (1243 -1295) who effaced any sign of his more distinguished predecessor’s Buddhist sympathies. A third and final stage added the broad 1st terrace (3, shaded buff) surrounded by an outward-facing open gallery (2) containing the celebrated bas reliefs scenes from Jayavarman VII’s dramatic rise to power and everyday life at Angkor during his reign. Sixteen Buddhist shrines (5) connected the first and second galleries (2, 6,) but were later destroyed, most likely in the same outbreak of Hindu iconoclasm.

In terms of Buddhist theology, the mural bas reliefs of the 1st gallery might correlate with Hinayana Buddhism’s “First Turning of the Wheel of Dharma,” accumulating “merit” by strict adherence in one’s daily actions to “right conduct,” dharma, over many generations. This was especially relevant after the usurpation of power in 1165, the Cham conquest of 1177 and Jayavarman VII’s restoration of the legitimate succession of divinely-anointed monarchs in 1181, the themes of the two Hindu epics. The 2nd terrace (8) might then correspond with the Mahayana, “Second Turning,” the monastic practice of self-negation through the pursuit of sunyata, the recognition of the “emptiness” of all things, which might explain why it was originally undecorated, as was the 2nd gallery of Angkor Wat except for its apsaras. The later Hindu bas reliefs of the outer, rectangular 2nd gallery (6) feature ascetics or sadhus, following the example of Shiva Bhikshatana, himself a hermit, perhaps providing the Hindu equivalent of the Mahayana sadhanas of renunciation, leading to moksha, or “release,” as Buddhist austerities did to nirvana, extinction of self. The open 3rd or upper terrace (9) and the face towers meditating over it would then provide a platform for Vajrayana’s “Third Turning” or yana of “efficient means;” whose closest architectural analogy would be the visualization of the mandala of a yidam, a personal bodhisattva representing one’s “Buddha nature.”

These three schools of Buddhism map, perhaps too facilely, onto the three “realms” of “temple mountain” cosmology, (detailed in appendix I,) understood, in this most philosophically “idealist” of religions, not as places in space but states of consciousness. Thus the narrative murals of the outer gallery, like those behind the “hidden foot” at Borobudur or their counterparts in the 1st gallery at Angkor Wat, would denote the boundary of the traditional, ten kamadhatu or “desire worlds.” The second gallery, originally austere, now carved with images of austerity, would then correspond with the eighteen, inward-turning rupadhatus or “form worlds,” like the inward-turning Mahayana sadhanas, its meditative and yogic practices, a transition for the aspiring bodhisattva to the four arupadhatu, or “formless realms.” These would be symbolized by the open, 3rd terrace, similar to the earlier open, upper colonnades at the Baphuon and Angkor Wat, where form is replaced by “a spaciousness without center or territory.” Thus, the Bayon could be seen as infusing new meaning into the familiar symbol of the “temple mountain,” reflecting the Khmer preference for a syncretic understanding of Hinduism and Buddhism which recast doctrinal differences as reflections or analogs of a similar underlying anagog, realized at a higher level, (much as Buddhism saw itself as an evolution from Hinduism and as the Mahayana regarded itself as a more advanced understanding of dharma than the Theravada.) The eventual addition of three terraces may have been intended to place the Buddhist Bayon squarely on a par with its two Hindu “temple mountain” predecessors, the Baphuon and Angkor Wat, or it could have marked a retreat towards a more acceptable form of Buddhism, not perceived as such a radical break with the Hindu past. The epigraphic gap towards the end of Jayavarman VII’s reign suggests the octogenarian monarch may not have been in full command of his faculties, his empire or its religious sympathies. This lacuna also means we have no way of knowing what considerations may have shaped the later development of the Bayon.

Not least among the Bayon’s mysteries is whether these three construction stages were conceived as a unified plan implemented over many years or were added piecemeal, reflecting shifting religious tendencies and political necessities, like the shrines added haphazardly at Preah Khan. Irregularities such as the uneven levels of the 2nd terrace do not prove that the rectangular gallery was added as an afterthought, any more than regularities, like the upapitha or 25-pada mandala which can be traced across all three terraces rules out the possibility it was extended post facto when a new terrace was added. If the 1st stage, the 3rd or upper terrace and redented, inner 2nd gallery, was conceived independently of the rest, it would be a structure without precedent, a trait, however, it would share with many of the world’s great ecclesiastical monuments – Rome’s Pantheon, Byzantium’s

Hagia Sophia, Paris’ Saint-Denis and, of course, Java’s Borobudur. The

eccentricities of the 3rd terrace or podium could be adduced as evidence

that it was never intended to be a discrete temple or, equally, that

Jayavarman VII’s was a sovereign/architect of exceptional audacity.

At first sight, the upper terrace appears to be a platform for the public

performance of the rituals of the theocratic Khmer state. It is dominated

by a massive conic shikhara approached along an eastern “processional

path” (detailed in figure 24,) which is fragmented into a series of eight,

small, enclosed structures, many without precedent in Khmer architecture.

This “liturgical axis” from the eastern gopura of the 1st terrace is lengthened

by the usual westward setback, here roughly 7.3% of the temple’s total

length, perhaps to accommodate whatever rites were conducted in these

atypical and sequestered spaces. The eastern side of the 3rd terrace

(9, outlined in blue) is more or less symmetrical with the western until an

awkward, but obviously purposeful, re-entrant angle forms a strip

(12b, between brown lines) next to the eastern edge of the redented square superimposed on the four arms of the cruciform terrace, a strip without a counterpart on the west, thereby introducing the usual, asymmetrical, westward offset. This indentation occurs at the narrowing where an antarala would join the mandapa to the garbagriha in a conventional, linearly-expanded Hindu temple. The crossbar or transept of the cruciform 3rd terrace is widened by the insertion of a second strip (12a, between brown lines) east of the north-south axis, also not present on its west. Together these strips (12a + b) account for the 7.3% westward offset and therefore equal the distance between the “threshold line” (11, broken brown lines,) where the temple’s width and length are equal, and the eastern edge of the 1st terrace (12c.)

This has several consequences: 1) the equal-armed Greek cross with superimposed square is lengthened on the east into a Latin cross with an upright longer than its crossbar. 2) West of the north-south axis, the square originally superimposed on the equal-armed Greek cross, makes the terrace triratha; it is, however, redented twice adding two rathas per quadrant, so those arms become pancharatha, with five rathas between their diagonals. 3) East of the north-south axis, in contrast, the square has been lengthened into an un-redented rectangle, so that the terrace remains triratha, a rectangle superimposed on a cross. The sections of the inner 2nd gallery around this rectangle are, however, redented and therefore isomorphic with the west. It is only with the insertion of the strip on the east of the north-south crossbar (12a) and the re-entrant angle (12b) that asymmetry is introduced. 4) In the extra space created by the inserted strip (12a,) two parallel face-towers (mauve) are placed flanking the east-west axis, absent on its west. 5) In addition, this broadened area east of the north-south axis can also accommodate two more face towers (also mauve,) usually dismissed as “anomalous” because they have no counterparts on the west. 6) The fact that the 7.3% off-set results wholly from the irregular design of the earliest-built 3rd terrace, yet aligns the corners of the later 2nd and 1st terraces (turquoise diagonals, in figure 23B,) might support the view that the Bayon was designed from the first as an integral, if irregular, structure.

A 5 x 5 upapitha mandala can be inscribed between the outer edges of the colonnades of the 1st terrace and the “threshold line,” (11, broken brown line.) Its grid’s six horizontal lines mark: 1, 6) the outer (northern and southern) edges of the 1st gallery and terrace (2, 3;) 2, 5) the outer edges of the colonnade of the rectangular (outer) 2nd gallery and terrace (6, 8;) and 5,6) the outer edges of the northern and southern towers of the east and west triple gopuras. The six vertical grid lines fall on the western edge of: 1) the colonnade of the 1st gallery and terrace (2, 3;) 2) the colonnade of the 2nd gallery and terrace (6, 8;) 3) the western towers of the 1st north and south triple gopuras; 4) the eastern towers of the 1st north and south triple gopuras; 5) the eastern edge of the colonnade of the outer or rectangular 2nd terrace and gallery (6, 8;) and 6) the “threshold line” (11, broken line.) In addition, a circular upapitha mandala with five rings would be tangent to the northern, western and southern edges of: 1) the colonnade of the 1st gallery and terrace (2, 3;) 2) the inner edges of their gopuras’ porches; 3) the rear wall of the outer (rectangular) 2nd gallery but not its colonnade (6;) 4) the outer edges of the medial shrines or face towers on the 3rd terrace’s north, south and west arms; and 5) the outer edges of the eight shrines around the central tower which also form the circular mandala’s round central pada. This does not prove that the architects used this mandala; the symmetry of Khmer temple architecture almost assures that regular grids will coincide with some repeated features of buildings, depending on which of them are measured. The combination of a square and circle is characteristic of Tantric mandalas, such as the vajrayana, vajradhatu, vajrayogina and vajrabhairava.

The central sanctuary (10) was originally a standard, square, Khmer shrine or prasat aedicularly expanded by the projection of four porches, as at Thommanon, here sub-shrines, in each of the cardinal directions to make a Greek cross. At some point during the temple’s three construction phases, four more shrines were added in the intercardinal directions, creating eight, partitioned rectangular shrines and eight interstitial triangular niches forming a circle. Presumably at the same time, the cella was transformed from square to round and surrounded by an ambulatory appropriate for pradakshina. Later still, another change of plans walled off this corridor on the east, blocking access to the liturgical path and rendering the ambulatory useless (see figure 24.) A conical tower or massif rose above these shrines but its reconstruction, like the one shown below from 1890, must remain conjectural, based as much on imagination as archaeological evidence. For example, the EFEO’s model (below) shows 1) sixteen shrines not eight, because it failed to distinguish the eight triangular niches; these are followed by 2) an aedicular tier with sixteen more shrines, except they end with portals not baluster windows; above these 3) sixteen, not eight, carved faces peer, each crowned by its own shikhara, like a court dancer; above these is another tier with 4) eight shrine aedicules; then 5) four more faces; and, finally, 6) a multi-tiered shikhara topping off this multi-tiered shikhara.

The circle is the ideal shape in Buddhism (as the square in Hinduism) because it radiates equally from a non-manifest center, rippling out like the initial drop or bindu. Almost every Buddhist stupa can be described as a series of rings narrowing to a tip but they display an impressive variety of ways to reach this. The Bayon has steeper sides than the original stupa at Sanchi or the hemispheric pagodas of Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, the center of Theravada Buddhism, but it is not as tapered as the soaring Schwezigon Pagoda in Bagan (c.1100) with its spire of multi-layered chattris or umbrellas (Burmese htis,) the origins of the pagodas of China and Japan. The Bayon’s profile seems to resemble more the earlier, bulbous or lotus bud shape stupa, e.g. the Bupaya Phya (10th Century) also at Bagan. The shikhara has the convex curve of the anda (Sans.> egg,) the “bell” of a stupa without its reverse, concave handle or finial. Perhaps its shape was also influenced by a much closer prototype, the convex shikharas of the Angkor Wat era with their curved antefixes smoothing the corners of their stepped aedicular tiers. Thus the rectilinear geometry of the Khmer temple mountain, generated by axial and lateral projection, as at the Baphuon, and aligned by concentric diamonds, as at Angkor Wat, seems, at the Bayon, partially

over-layed with a Buddhist radial impulse. These three

systems: (a) axial and lateral projection (b) interlaced

diagonals and (c) radial projection – can be illustrated

and compared by the positioning of the Bayon’s

distinctive face towers, analyzed in

figures 23A, 23B and 23C on

the following pages.

FIGURE 22: ANALYSIS OF SITE PLAN,

BAYON (1181-1220)

RECONSTRUCTION OF BAYON (1181-1220)

ÉCOLE FRANCAISE D’ EXTREME-ORIENT (1890)

34