Preah Khan:

A Horizontal Temple Mountain

Jayavarman VII built two monumental Buddhist monastic complexes at Angkor, Ta Prohm (1186,) dedicated to his mother, and the even more ambitious, Preah Khan (1191,) honoring his father, a Khmer practice as old as Indravarman I’s Preah Ko (880) and Lolei (893,) built by his son, Yasovarman I, both at Roluos, the former Hariharalaya. Jayavarman VII also built another large monastery, Banteay Kdei, between the Srah Srang Baray and southeast corner of Ta Prohm, as well as two smaller “forest temples,” Ta Nei and Ta Som, for itinerant ascetics and hermits who often followed heterodox practices. Preah Khan’s very detailed, though possibly exaggerated, dedicatory inscription found at the site, records that the complex contained shrines for no fewer than 515 deities, 1,500 resident monks to perform the requisite rites on 139 days each year, supported by 75,000 “bonded laborers” (serfs or slaves) who provided the temple’s income by farming the surrounding plain. The monastery also commemorated the site of Jayavarman VII’s final victory over the Cham in 1181 and was adjacent to the 3.5km x 1km Jayatataka Baray, built specifically for it,with an island temple, Neak Pean, at its center, which also honoredhis father, the last such reservoir constructed at Angkor and another traditional obligation of a Khmer monarch.

Preah Khan was designed for monastic life in the stratified Mahayana and possibly Vajrayana Buddhist orders or lineages, a lifetime abiding by the pratimoksha, the 227 vows of an ordained monk, and devoted to achieving the disa sila, the ten precepts, perfections or paramitas needed to become a bodhisattva, someone who having achieved prajnaparamita, a continual state or enlightenment, would delay his entry into parinirvana, non-existence, to teach others the path for escaping the suffering of living. (For a description of the ten paramitas and five panca-margas, see appendix III.) Buddhism adopted the Hindu symbolism of Mt. Meru to represent the thirty-one (or thirty-three) discrete stages of consciousness or “modes of being” delineated in its rigorously idealist ontology, (where human being is ranked twenty-seventh.) These include eleven kamadhatu or “desire realms,” equivalent to sea level and the mountain itself, as well as eighteen rupadhatu or “form realms” and four arupadhatu or “formless realms,” thousands of miles above its summit. Preah Khan might therefore be thought of as a horizontal temple mountain where spiritual attainment was measured not by upward ascent but linear progress along its liturgical axis, marked by the more than twenty terraces, gopuras, shrines and thresholds crossed before reaching the sanctuary at its center. This modest tower, so different from the soaring peaks or shikharas of Hindu temples such as Angkor Wat and Kandariya Mahadeva, denotes the place (or non-place) where the monk aspiring to “Buddha consciousness” detaches himself from the horizontal or terrestrial dimensions, the limits of personal “territoriality” and form, and enters the “formless” worlds of the arupadhatu, a state of pure verticality, the “updraft to extinction,” as it were, and a “return of the womb” or the bindu. As with most other aspects of Khmer life, we have little evidence about Preah Khan’s daily use and can only compare it with Buddhist texts and practices elsewhere.

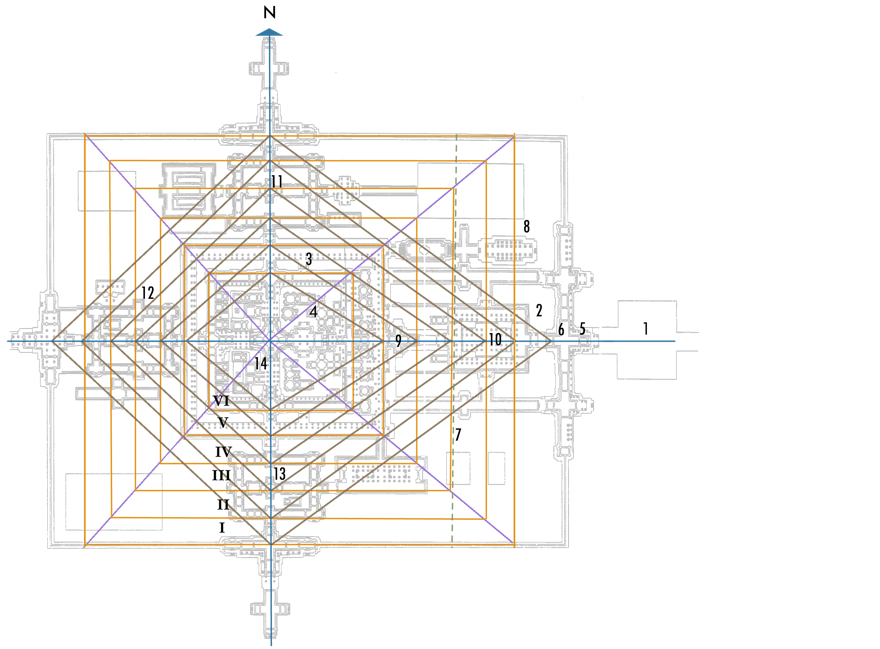

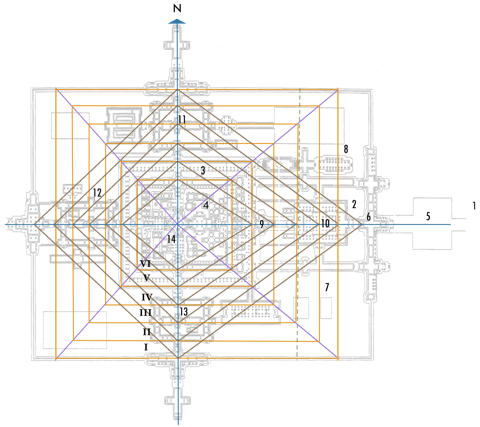

In place of Angkor Wat’s three vertical levels or terraces, Preah Khan has three enclosures (2,3,4) inside a fourth outer enclosure (1) measuring 800m x 700m which contained a small city supplying the material resources for the metaphysical pursuits inside the other three. Monks and visitors would presumably have arrived by boat at a landing stage on the western end of the Jayatataka Baray, perhaps representing a purifying passage from the profane to the sacred world, washing away the samsaric defilements of egotism and attachment, leaving unblemished anatta, not-self. This would then have been a metaphoric journey for the dead self and the liberated soul, analogous to the voyage across the River Styx or journey to the Isle of Avalon in Western mythologies and the lotus rising through the muddy waters of a pond to blossom on its surface in the sunshine of enlightenment in Buddhism. A raised causeway led from the baray to a moat, another common symbol for purification, representing the seven oceans ringing Mt. Meru, protecting it from defilement from the impure castes and “modes of consciousness” below. A terrace with a naga or “rainbow” bridge crossed this moat, another metaphor linking the monsoonal rains essential to the fertility of the Khmer lands to the heavens which granted them, as well as, the liquefaction and liquidation of the material body as it evaporated into the “subtle” or “spiritual" one. This bridge and terrace led through the three 4th east gopuras, large enough for carts to pass, and the 4th enclosure wall. This was supported on the outside by seventy-two, 5m tall garudas, the half-bird, half-man mount or vehicle of Vishnu and traditional foe of nagas, establishing a cordon sanitaire between the spiritual within and chthonic forces without, while figuratively lifting the temple off the Angkorian plain onto that of Mt. Meru.

The east-west “liturgical axis” then passed through the 4th enclosure (not shown in figure 20 but illustrated in Preah Khan’s photo gallery), past a large “House of Fire” holding the still obscure “Sacred Flame,” across another naga terrace (5) through the 3rd east gopura (6) into the 3rd enclosure (2) filled with shrines, terraces and pools and a unique two-story building, reminding some of Greek architecture (8) whose use remains a mystery. The 3rd enclosure’s length is 23.4% greater than its width* and is dominated by four large structures with similar dimensions adjacent to its four cardinal points. The building on the east (10) was a quadripartite, fenestrated, hypostyle hall, roofed with tiles or stone slabs, reminiscent of the terraces on the east of Ta Prohm, Banteay Kdei, Angkor Wat and the Baphuon. It has been called the “Hall of Dancers” because of the exceptionally, well-carved and numerous apsaras or wind nymphs on its friezes and lintels and by analogy with the natamandir or natamandapa, an open “dancing floor” in front of some Hindu temples, most famously, the Sun Temple at Konark. Although a pillared hall with four small courtyards does not appear an ideal design for dancing, it could have been used for ritual dances or trances to purge monks and pilgrims of the grasping self of the kamadhatu, the “desire realm,” by discovering the “self-delighting” consciousness of the rupadhatu. (This is also represented by apsaras in the 2nd gallery of Angkor Wat, who have risen above the world of myth, history, kings, gods and mortals, depicted in that temple’s 1st gallery bas reliefs.) In this view, the three enclosures would correspond with progress through the “three worlds” of Buddhist cosmology towards the awareness of sunyata, the emptiness at the center of all things and last step before nirvana, non-consciousness and non-existence. The northern shrine (11) was dedicated to the Hindu “Great Lord” or Shiva, the “Destroyer” or “Transformer,” the western (12) to Vishnu, the “Preserver,” and the southern (13) to Jayavarman VII’s father, Dharanindravarman II, in his posthumous form as Avalokitesvara (Khmer > Lokesvara,) the Mahayana “bodhisattva of compassion” and one of the leading candidates for the enigmatic “face towers” of the Bayon and Angkor Thom. That king’s posthumous name was actually Manish Kala or Yama, the god of death, which though logical, hardly portends an ascension to Mt. Meru for the deceased. These shrines’ inclusion in the 3rd but not the 1st or 2nd enclosures shows how Buddhism positioned Hinduism as an authentic but less advanced revelation of dharma, analogous to the role of the Old in the New Testament.

The 3rd enclosure (2) is divided horizontally into three equal bands, each the width of the 1st enclosure (4;) accordingly, it can be subdivided into fifteen equal, horizontal strips between its northern and southern walls. The 1st enclosure would occupy the central five bands (not shown on figure 20 but on figure 21.) The outer ten bars are divided on the site plan by twelve ocher lines which fall on: the 3rd enclosure's (2) north and south walls [1,15;] the outside edges [2,3,14,13] of the outer and central galleries and the inside edges [4,12] of the inner galleries of the Shiva and

ancestors' sub-shrines (11,13,) as well as, the outer edges of the 2nd [5,11] and

1st [6,10] enclosures Diagonals (purple lines) drawn from the center of the

sanctuary (and axial crossing) through the eight corners of the 1st

and 2nd enclosures to their intersection with the 3rd enclosure's

north and south walls, also pass through two pillar altars (balipithas

or socles) in the northwest and southwest courtyards of the 1st

enclosure, (see 1st enclosure details on figure 21.) The angles

between the two pairs of purple lines differ slightly because of

the enclosure's westward off-set.

Vertical lines, (also ocher,) connecting the intersections of

the purple diagonals with the twelve horizontal ocher lines

between the 3rd and 1st enclosures (2,4,) fall, on the east: along

the outer, center and inner rows of columns of the "Hall of Dancers"

(10;) on the outer edge of the protruding 2nd east gopura (9;) and on

the eastern edges of the 2nd and 1st enclosures (3,4;) On the 3rd

enclosure's west, they span: the outer (western) edges of the Vishnu shrine (12) and

its mandapa; the center of its cella; the inner edge of its eastern gallery; as well as, the western edges of the 2nd and 1st enclosures (3,4.) The "threshold line" (broken gray line,) the point where the length of the 3rd enclosure (2) equals its width forming a square, falls on the inner (western) edge of the "Hall of Dancers" (10,) which is also the 2nd vertical, ochre line from the east. Thus, the ochre lines outline six rectangular, ”virtual" or "horizontal" terraces (numbered with Roman numerals I-VI:) the 1st enclosure (4,) containing the central shrine (14) occupies the innermost or "upper," "virtual" terrace (VI,) similar to a "temple mountain;" the 2nd enclosure (3,) the "terrace" beneath that, corresponds with the 5th "virtual" or horizontal terrace (V,) etc. In common with other temples, such as Angkor Wat, as the rectangular terraces or enclosures draw closer to the axial crossing and central shrine, the more closely they approximate a square.

The four sub-shrines (10,11,12,13,) as well as, the 2nd (3) and 1st (4) enclosures are positioned within the 3rd enclosure (2) by six concentric diamonds (brown lines) drawn between the intersections of the cardinal axes and, on the north and south: the outer edges of the six horizontal terraces (I-VI,) corresponding with: 1,2) on the north and south, the enclosure walls of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd enclosures (4,3,2;) the outside edges of the outer two galleries and inside edges of the inner galleries of the Shiva and ancestor's shrines (11,13;) 3) on the west, the axis' intersection with the 3rd enclosure's western wall and the western edges of the outer five, rectangular "virtual terraces" (I-V) - four across the Vishnu shrine (12) and the fifth, the 2nd enclosure's (3) western wall; 4) on the east, the axis' intersection with the inner porch of the central 3rd east gopura (6) and the eastern edges of the outer five "virtual terraces" (I-V) - three across the "Hall of Dancers" (10,) the outer edge of the protruding 2nd east gopura (9,) as well as, its inner edge, the eastern edge of the 2nd enclosure (3.) These six concentric diamonds (brown) are elongated on the east reflecting the 23.26% westward off-set. 1) The outermost diamond positions the four sub shrines’ (10,11,12,13) eight outer corners; 2) the second diamond in is tangent to the four corners of the 2nd enclosure (3;) 3) the next or third diamond passes through the four sub-shrine's eight inner corners; 4) the fourth diamond encloses the four corners of the 1st enclosure (3.) Since it intersects the corners of two chambers projecting from that enclosure's northern and southern walls, this indicates they are the ends of the incomplete 1st east gallery, (see 1st enclosure detail, figure 21.) 5) The fifth diamond links the outer edges of the 2nd north, south and protruding east gopuras, 6) while the innermost 6th diamond connects the outer edges of the 1st north and south gopuras and 2nd west gopura with the inner edge of the protruding 2nd east gopura, the 2nd enclosure’s eastern wall.

*This site plan for the 3rd enclosure of Preah Khan demonstrates the fallacies which can arise from measuring the dimensions of Khmer monuments from published sources with the inevitable distortions of generations of reproduction and of using a magnifying glass as a surveying instrument. It is taken from Ancient Angkor by Michael Freeman and Claude Jacques (River Books, Bangkok, 2009) whose generally admirable text describes its dimensions as 200m x 175m, a width 87.5% of its length (though, on its face, it seems unlikely the Khmer laid-out their temples in units of 25m.) The plan beneath this statement measures 86mm x 66mm or 76.74% with a westward offset of 23.26%. It happens that the current, mean obliquity of the earth’s axis, its tilt from the ecliptic or plane on which the sun appears to circle the earth, is 23°26’12” How could this number be fortuitous to the numerologically inclined Khmer? Easily. Since the earth’s tilt oscillates by 2.4° over a 41,000 year period, it is currently decreasing by 47 arc seconds a century. This means that since the time Preah Khan was built, the planet’s tilt has decreased 8 x 47 = 376 arc seconds = 6’16” and its obliquity in 1191 was 23° 32’ 28”. Is this within the range of tolerance of a ruler, pencil and tourist’s guide book – or Khmer astronomer? And, more importantly, did they care?

“HALL OF DANCERS,” 3RD ENCLOSURE, PREAH KHAN (1191)

FIGURE 20: ANALYSIS OF SITE PLAN,

PREAH KHAN (1191)

1 – 4th enclosure

2 – 3rd enclosure

3 – 2nd enclosure (see figure 21)

4 – 1st enclosure (see figure 21)

5 – Terrace, end of causeway from the baray

6 – 3rd east gopura with 5 entrances

7 – “Threshold line,” 23.26% westward off-set

8 – Two-story building

9 – Protruding 2nd east gopura

10 – “Hall of Dancers”

11 – Shiva shrine

12 – Vishnu shrine

13 – Ancestors’ shrine

14 – Central tower and shikhara

I – VI – six “horizontal” terraces

FIGURE 20: ANALYSIS OF SITE PLAN,

PREAH KHAN (1191)

1ST WEST GOPURA, PREAH KHAN (1191)