Linear Contraction and Expansion: The Kandariya Mahadeva Temple

The problem encountered at Phimai of integrating the disparate elements attached to the central shrine and scattered around its two inner enclosures received what many regard as a definitive asolution more than a half-century earlier at the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple (c.1030) at Khajuraho in today’s Madya Pradesh, long recognized as a pinnacle of Indian ecclesiastical architecture. Built by the Chandela Dynasty, it is dedicated to Shiva in his aspect as “Great God of the Cave,” an appellation referring simultaneously to that god’s life as an ascetic in the caves on snow-covered Mt. Kailasa and his probable origin as a chthonic fertility deity worshipped in his aniconic form, the linga in the garbagriha, the cave-like “womb chamber” beneath the shikhara’s peaks. This appellation similarly joins the god’s aethereal austerity with the seismic forces of the Nataraja, ”Lord of the Dance” and “Destroyer of Worlds,” unifying Shiva’s role as purging the degenerate former-epoch or mahayuga,while laying the basis for a fertile new age. Shiva’s complex, sometimes contradictory attributes may derive from the syncretic origins hypothesized for the Hindu Trimurti, sky gods of the nomadic Indo-Aryans assimilated with indigenous Dravidian agrarian deities. The first Khmer temple mountain, Ak Yom (700-725,) was dedicated to Shiva in a similar aspect as Gambhiresvara, “God of the Hidden Depths” or “Hidden Knowledge.” Similarly, the god appears as Bhikshatanamurti or “Supreme Mendicant,” a sadhu or ascetic wandering the charnel grounds, naked in the company of demons and outcasts, as penance for severing Brahma’s fifth head (or, in other versions, for killing a brahmin.) In his most fearsome aspect, Bhairava, Shiva represents annihilation as the ultimate reality and reappears in this nihilistic aspect as Heruka or Vajrabhairava in Tantric Buddhism, defying even dharma, divine law, through ritual defilement to affirm sunyata, the emptiness and ephemerality of all things, “beyond good and evil.” Private devotional statues or yidams of these transgressive deities, found at Angkorian sites from as early as the 10th Century, evidence that members of the Khmer elite followed these occult practices long before Mahayana Buddhism became the state religion under Jayavarman VII (1181-1220.) Buddhism at Angkor is discussed in section XIII under "Vajrayana Mandala Visualization" and throughout section XIV, "An Architecture Without Form or Dimension."

The Kandariya Mahadeva Temple has been as intensively studied as almost any building in the world, its complex structure mapped onto multiple mandalas,as well as,plane, rotational and fractile geometries, demonstrating, if nothing else, the mathematical sophistication of its sthapakas – or their modern exegetes. These brief notes will limit themselves to the temple’s most frequently remarked feature: the unification of its linear components into a single massif rising around the summit of its shikhara and their complementary eastward flow onto the surrounding plain.

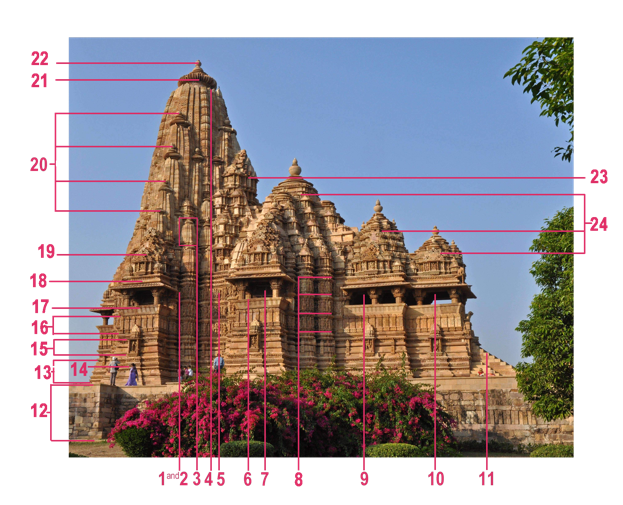

FIGURE 6: KANDARIYA MAHADEVA TEMPLE (c.1030)

A GUIDE TO NAGARA (NORTHERN INDIAN) TEMPLE TERMINOLOGY

The temple’s vertical profile, figure 6, from the kalasa or urn finial on its tower, through its urushringas or “shoulders,” its partially-emerged aedicules or sub-peaks, to the phamsana, pyramidal roofs of its three mandapas, does not plot a straight line so much as an asymptotic curve (y = 1/x or y = xn where n< 0.) Extrapolated along the y- or perpendicular axis, its slope approaches the vertical at the garbagriha and the shikhara’s peak, pointing infinitely above the earth; extended along the x- or horizontal axis, it approximates the line of the varandika or cornice paralleling the ground or terrestrial plane. Thus, the temple’s outline leads the eye from the earthbound and material through the “form” and “formless” realms to pure ascent and dimensionless non-existence, moksha.

The pidas or layers of its three overlapping phamsana roofs form stacks rising towards the sukanasa, their juncture with the shikhara’s cascade of urushringas, a layering continued downward through the jangha or temple’s “thighs” by the celebrated, horizontal bands of erotic friezes, to the multiple moldings of the vedibandha and adhisthana, the temple’s lower walls; even the eastern staircase can be read as a phamsana roof seen from above. In contrast, the roofs of the antarala, mandapa and ardhamandapa or eastern porch at Phimai are barrel-vaulted shalas.

1) Linga/ lingam, aniconic Shiva image and altar

2) Garbagriha, “womb chamber,” sanctuary or shrine

3) Sekhari aedicule with vertical bands or urushringas or shoulders, here atop a stambha or column; the temple contains 84 of these peaks, not including the shikhara itself of which they are replicas.

4) Shikhara/ sikhara, “mountain peak,” spire, here a 31m sekhari tower with seven rathas or vertical angles

5) Antarala, vestibule linking the shrine and the mandapas

6) Porches, transepts lighting the garbagriha and mahamandapa

7) Mahamandapa/ gudhamandapa, large, enclosed hypostyle hall with porches

8) Jangha, the temple’s “thigh” or “calf,” a zone of solid wall, here with 3 tiers or registers of bas reliefs depicting gods,

goddesses, nymphs and mithunas or erotic couples, separated by moldings.

9) Mandapa/ mantapa/ sabhamandapa here, an open-sided assembly hall

10) Ardhamandapa, a “half-pavillion,” mukhamandapa or “outward-facing” mandapa, an open-sided, entrance porch,

11) Eastern stairs to the ardhamandapa from the jagati, plinth or platform.

12) Jagati/ upapitha a raised platform, foundation or stereobate on which a temple’s base and superstructure sit

13) Adhisthana, consisting of the temple’s base molding sequence, upana, khumba/ khura, kumuda, kapota

14) Antatapati, a molding with a processional frieze of asva (horses,) gaja (elephants,) warriors, hunters, etc.

15) Vesana-pattika, a zone within the adhisthana or with niches containing deities

16) Vedi/ vedika, “fence,” originally surrounding a stupa as at Sanchi, the "blind" railings or balustrades of porches and

shrines; also altar

17) Kaksasana/ Asanapattaka, the inclined “seatbacks” of the porch’s benches

18) Varandika, entablature or cornice , a series of kapota/kapotali, eave moldings, and uttara, architrave

19) Pediment, the triangular covering at the end of a panjara, gable, dormer gavaksha, nasi’s horseshoe arch with a nnntympanum with a narrative scene, often from the Hindu epics

20) Urushringa a temple’s “shoulders;” here four tiers of sekhari aedicules, partially emerged from the shikhara of

which they are replicas

21) Kalasa/ kalasha, a vase-shaped finial at the top of a shikhara or tower

22) Amalaka, lotus petals or grooved solar disk below the finial

23) Sukanasa, the temple’s “parrot’s beak,” or nose, the dormer connecting the shikhara with the roofs of the antarala

mahamandapa

24) Phamsana, a multi-pida or tiered pyramidal roof over a mandapas; a jagamohana in Odisha