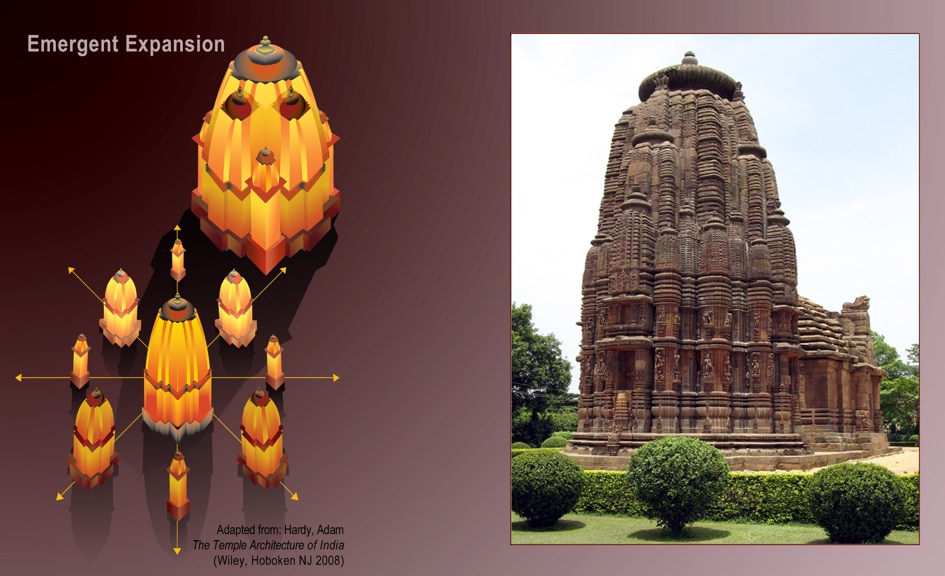

Emergent Expansion:

Rajarani Temple

“.nnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnc”

panchratha sekhari

prasada

triratha urushringa

sekhari stambha

FIGURE 9: EMERGENT EXPANSION ANALYSIS. LEFT; RAJARANI TEMPLE, BHUBANESWAR (1100,) RIGHT

4 5 1)

CHENNAKESHAVA TEMPLE, SOMANATHAPURA, KARNATAKA (1268)

The sthapakas or sthapatis (we can’t be sure which would have been responsible for introducing these innovations) realized that they could increase the number of facets and hence perches for shrines for deities and niches for sculpture exponentially, if aedicules emerged only partially from the core shrine. Adam Hardy demonstrates this process with his usual clarity using the shikhara or tower of a Northern Indian or Nagara-style temple, a simpler version of the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple in figures 1, 6 and 7. In his illustration, at the left in figure 9, adapted for this introduction, the core of the tower is a sekhari shrine, a redented square tower, the five rathas of whose walls are continued vertically to join at the shikhara’s peak and amalaka (the middle tower of the nine, lower left.) The core shrine, it should be noted, is the same as the standard Khmer shrine, a square with two slightly-emerged, superimposed crosses – technically pancharatha. This central mass then emanates four triratha, sekhari aedicules, smaller versions of itself, which emerge only half-way out of the shrine’s “torso,” hence their name, urushringas or “shoulders.” The corners between these urushringas are filled by four, fully-emerged, nearly free-standing, sekhari stambha aedicules, that is, a stambha or pillar acting as the ground story capped by a miniature convex, striated sekhari tower shrine. Since the emergent aedicules are each projections of the shikhara’s original five rathas, the expanded tower remains pancharatha.

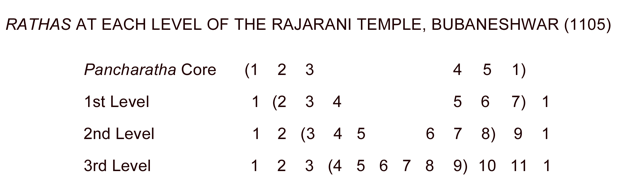

The Rajarani Temple (c.1100) in Bhubaneshwar, the capital of Odisha (formerly Orissa) state on the western coast of the Bay of Bengal, provides an example of emergent expansion in a different Nagara or Northern Indian architectural idiom from that at nearby Khajuraho, sometimes referred to as the Kalinga style after the ancient name for this region. The temple’s dedicatee is uncertain; its name derives from the local reddish-yellow sandstone used in its construction. The theme of its sculptural decoration seems to be the marriage of Shiva Nataraja, “Lord of the Dance,” and Parvati, “She of 1,000 Names,” surrounded by mithunas, erotic couples, and nayikas or nymphs. For this reason, it is known locally as the “Love Temple.” In the Odisha tradition, the shrine surrounding the garbagriha is called the bada, deula or deul which together with its convex tower is called a rekha deula or deul. The tower itself is called a vimana (Nagara, shikhara), as in Dravida usage, a less restricted term for a god’s vehicle than ratha, which specifically means a cart or chariot; therefore, it could encompass the “flying palaces” of early Khmer shrines and Kubera’s magic pushpaka. The link between a temple’s tower and the vehicle of a god confirms that a vimana and the shrines placed around it were considered the earthly “helipads” of the resident deities. The Rajarani Temple’s vimana is ringed with partially and nearly fully-emerged aedicules, that is, re-instantiations of itself, analogous to the urushringas in other sekhari shrines. This basic aedicule is the already familiar pancharatha, Khmer prasat module, a square with two, broad but very shallow crosses superimposed on it. The vertical projections or rathas are not solid walls or gavaksha meshes, but horizontal layers of thin teeth, a motif continued to great effect in the temple’s varandika (cornice) and adhisthana (foundation.) The profile of the vimana is cylindrical with steep sides and a relatively flat trough traced along its crown, giving it and its aedicules the appearance of turrets or cones, perhaps similar to how the Bayon’s tower may have looked. (Possible reconstructions of the Bayon’s shikhara are included among the twenty-five photos in the album on that temple.)

The Rajarani’s “aedicular expansion” follows a straight-forward pattern: on each of the three levels of its vimana a pancharatha aedicule, like the core, is projected between the kanika, (karna) rathas (or corner pagas) of that level. Its progression is schematized in the following table where the emergent pancharatha aedicules are contained within parentheses, (including both corners for a total of six) and the vertical projections, rathas or pagas, for each level increase from the initial five of the hidden core to all eleven on its 3rd or lowest level; the outer, two kanika rathas are both numbered “1.”

1) On the upper or 1st level, the projected pancharatha aedicule consists of the anuraha rathas (2, 7) and raha rathas (3, 6) of the notional core, plus a broad central strip which projects between the raha rathas ( 4, 5) making the level saptaratha; a crouched ascetic or gargoyle sits above it. 2) The pancharatha aedicule of the 2nd level (its rathas 3 – 8) is a half-emerged turret, the equivalent of an urushringa; its unity is emphasized by its crowning half-amalaka with its traditional finial, a kalasa or vase. 3) On the lowest or 3rd level of the vimana: a) the central pancharatha aedicule (rathas 4 - 9) has emerged so far in front of the 2nd level, it could almost be a free-standing aedicule; its five facets are so close, they look rounded (except for their flat projecting sides.) b) The kanika and raha rathas of the core (1, 3, 10, 1 on the 3rd level) have also bulged into nearly fully-emerged aedicules with miniature pancharatha bites taken out of their corners and their own amalakas. c) The smaller, angular anuraha rathas (2, 11) have become triratha tapered towers with amalakas higher than those on either of their sides. 4) A prominent varandika or cornice runs beneath the 3rd level where the teeth thicken into seven continuous, though redented, moldings. Here the three projections of the 3rd level’s pancharatha aedicule are reduced to one and the deula / deulre returns to the saptaratha shape of its 1st level; these are articulated by: (a) large, rounded kanika rathas (b) a sharp, pointed, anuraha ratha (c) a large, rounded, raha ratha and (d) a flat central panel projecting across the cardinal axes, resembling the bhadra or vertical cascade of panjara roofs, split gavakshas windows or nasi of a Dravida vimana. 5) Beneath this cornice, a frieze is carved on the flat outer faces of the large kanika and raha rathas with figures in tribhanga poses and erotic couples discretely hidden in the re-entrant angles with the smaller anuraha rathas. The space between the central raha rathas becomes a pilastered tilaka or shrine with a row of gods. 6) A second cornice and frieze are then repeated on the temple’s walls, jangha or pada/padam. 7) The horizontal bands or molding of the varandika, jangha and pitha (adhisthana or base) anchor the soaring vimana to the deula/deul or shrine below and unite it with the layered pidas of the pyramidal phamsana roof of the attached jagamohana, a mandapa in Odisha usage.

A comparison of the two temples in Figure 9 shows how a similar process of "emergent expansion" can produce markedly distincteffects and affects. The most obvious difference is the curves of the two shikharas' profiles. In the left-hand diagram, a simplified version of a sekhari shrine like the Kandariya Mahadeva, the shikhara's sides curve steadily inward like a parabola which would reverse above the tower's crest were they not “stoppered” by the amalaka. At the Rajarani Temple (on the right) the sides are even steeper but flattened across its top, so the vimana appears truncated or blunted, more like a linga, turret or butte than a peak. In addition, the number of rathas in the sekhari temple diagram (on the left in Figure 9) remains the same - five or pancharatha - broadening or expandinge rather than multiplying as they descend by reducing the rathas of its emergent aedicule from five to three. In contrast, at the Rajarani Temple, a pancharatha aedicule emerges immediately from the pancharatha core at the peak (level 1,) while the two, lower emergent aedicules are also pancharatha, increasing the total number of rathas from five to seven, nine and eleven. Furthermore, by its 3rd (lowest) level, the aedicules emerging from the kanika (corner) rathas of each of the three axial projections have tiny pancharatha dents as well, producing a fringe of 7 x 5 or 35 miniature rathas,(counting both corners,) a fraying finally hemmed by the strongly saptaratha upper cornice. The overall impression can suggest dishes stacked around the core rather than emerging from it. These contrasting strategies for “aedicular emergence” are roughly analogous to what Adam Hardy’s has termed “expanding repetition” (the sekhari example) and “progressive multiplication (the rekha deula.)

The proliferation of tower types devised by Indian temple architects has led their temples to be classified by the profile of their shikharas or vimanas. In the Nagara or Northern Indian tradition a shikhara can take three basic shapes: latina, with a fixed number of vertical spines, sometimes made of gavaksha meshes; sekhari / shekhari also composed of vertical strips from which sekhari aedicules and stambhas emerge, like the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple, and bhumija, made with stacks of aedicules between vertical latas. A related type, phamsana, made from a pyramidal stack of pidas

kapotas, kapotalis, eaves) is reserved for the roofs of mandapas, the assembly hall attached to the garbagriha and shikhara’s east. In Odisha (Orissa,) in addition to the rekha deula described above, there are also pida deula and khakhara deula, with pyramidal and truncated outlines, respectively. In the Southern Indian or Dravida tradition, a tower could have up to thirteen talas or tiers of aedicules, as at the Ranganathswamy Temple, and as many as sixteen projections or facets, for example, the stellate Hoysala Chennakeshava Temple (1258) in Somanathapura, pictured above. Thus, a tower’s overall profile could be convex (ogival,) pyramidal or a parallelogram with any number of vertical projections and horizontal tiers but each in its distinctive way symbolizing Mt. Meru.

*In the context of Khmer “aedicular projection” or “replication,” both these examples suggest that “aedicular emergence” might equally be seen as “aedicular merging,” “reabsorption” or even “returning.” Despite the arrows in the diagram, the urushringas could as easily be read as clustering around and clinging to the core as escaping its embrace. Why are these aedicules only “partially emerged,” why not totally projected like the outer towers of a Khmer panchayatana? This ambiguity reflects the interlinked movements of emission and reabsorption inherent in Indic philosophy's cyclical ontology. Indeed, most religions seem to share a centripetal tropism, a cosmic "regression to the womb," as it were. Hinduism and Buddhism seek a return from the manifest (sakala)and "dependently-originated" to their non-manifest(niskala,) uncreated origin. The only way to escape or be released (moksha) from the "suffering" of individuation and the transience of becoming is through the extinguishing (nirvana) of consciousness, a kind of mental suicide resulting from the mind’s awareness of its own sunyata or "emptiness." Similarly, the "original sin" of the Bible was eating the "forbidden fruit of the tree of knowledge," seeking independent human understanding rather than humbly accepting what one's creator had given. Therefore, the way back to this lost Paradise, this oneness with God, was the via negativa, repentance for autonomous thought and renunciation of active intelligence, in favor of mental quietude or anesthesia and unquestioning faith. Thus,the real question for theodicy might not be the origin of evil but of creation and differentiation, if the point of being is simply to return to primal oneness and non-existence. Islam, which means "submission," traces a similar circular ontology and eschatology away from and back to "pre-creation;" an "arc of descent"(qaws-al-nuzul,) where Allah shares his "hidden treasure" by creating mankind and an "arc of ascent"(qaws-al-su'ud,) where humanity gratefully return through Sufiism's fana ("self-annihilation.") Alas, the "arc of descent" seems irreversible; humans can't seem to stop having original thoughts, inventing new gods, dogmas and theories, even sprouting wings “God didn't give them” and flying economy; the universe seems set on expanding centrifugally and the Third Law of Thermodynamics keeps on scattering entropy.