Brick Sanctuary at Baking

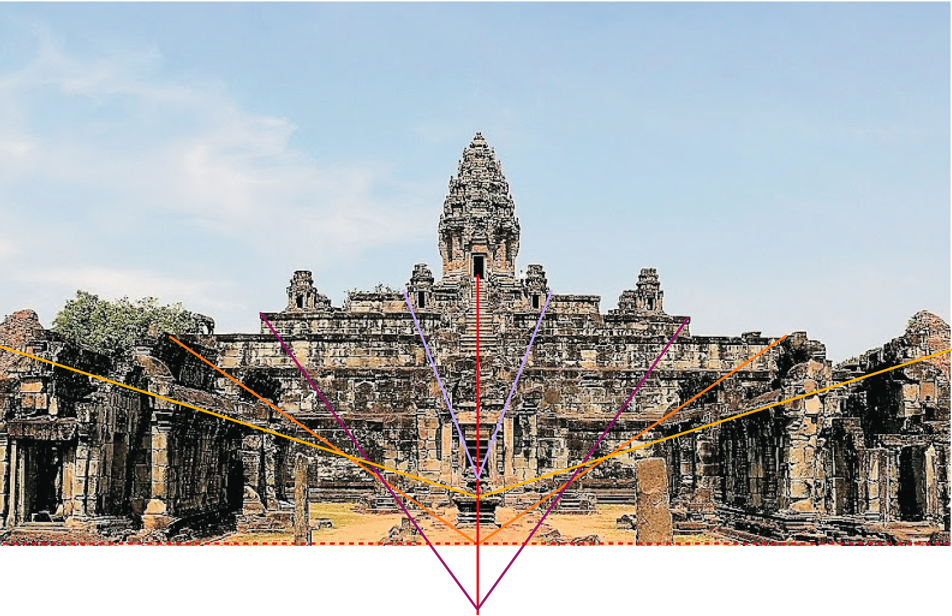

FIGURE 16: VIEW FROM THE BAKONG’S EASTERN “THRESHOLD LINE,” 6 ON THE SITE PLAN, FIGURE 15

FIGURE 14: VIEWS ALONG THE “LITURGICAL AXIS,” BAKONG (881)

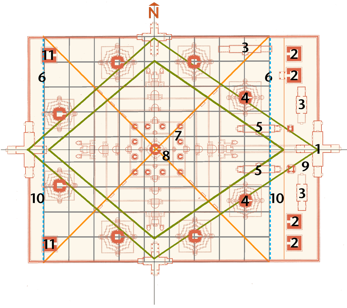

FIGURE 13: ANALYSIS OF SITE PLAN, BAKONG (881)

ASURAS OR DEMONS

(ONLY REMAINING BAS RELIEF,) BAKONG (881)

The enclosure’s asymmetry or elongation on the east would be of merely geometric interest if it did not have the potential to modulate the experience of worshippers as they proceeded along the Bakong’s “liturgical axis” towards the shrine and Shiva linga (traced in red at the center of figure 14 above.) Entering at the 1st east gopura (1 in figure 13, at right) they would find themselves outside the mandala’s “sacred square” with the pyramid and sanctuary or cella at its center. Their progress across the enclosure and up the pyramid would therefore symbolize their quest for satori or enlightenment and its levels, thresholds and stages of that progress. Along this route, their vision would initially be focused by the two long rectangular buildings (5,) the “sacristies” or “libraries,” in a narrow vector (maroon) limited to the eastern steps, the twelve shrines (7) of the 4th terrace and the tower of the 5th (8,) their path and goal. As they progressed past the crematoria (2,) memento mori of the samsaric selves they were abandoning, through the purifying flames of the border vajra strip (10) and across the “threshold line” (6, broken turquoise line) into the mandala’s sacred space, their view would widen to include the 3rd terrace (orange vector) and the two eastern peripheral shrines (4.) Once, they were past the “libraries” (5) and stood before the Nandi shrine (at center,) they could see the full breadth of the enclosure (yellow vector) and all four of its northern and southern shrines. Upon reaching the foot of the eastern steps, however, the mass of the pyramid would block the view (purple vector) of anything but the five flights of stairs ahead of them to the central tower, now lost from view. Only upon attaining the 4th terrace, (7) would they again be able to see the entire tower and have a 360o view of the enclosure, its asymmetrical eastern and symmetrical western halves, its full complement of eight peripheral shrines, standing around it like guardians, its three enclosures and beyond that the pedestrian, mundane world, which from this new, elevated perspective, might well seem defamiliarized, very distant, even unreal or maya. The slight setback of the central tower on the 5th terrace (8), the resultant asymmetrical advance of the front four shrines on the fourth terrace (7) and the elongated diagonals of the inner corners of the four eastern towers and their plinths (olive lines) might induce a kind of “forced perspective,” exaggerating the 12% setback of the shrine and terrace and hence the viewers’ distance from the 1st east gopura where they first left the quotidian world. This view would reverse what they had just experienced climbing the Bakong: the contraction of distance as they were drawn from the rectangular enclosure into the “still center” of the square, 9x9-pada mandala.

The Asymmetry of

Khmer Temple Mountains

Almost all Khmer temples are, like the Bakong, offset to the west, (or, exceptionally, to the east, in the case of the west-facing Angkor Wat,) so their two sides are asymmetrical. Their western two quadrants are often two squares and hence are entirely contained within the sacred grid of the governing mandala; (at the Bakong, Phnom Bakheng and Baphuon the mandalas have symmetrical strips on either side.) Their eastern sides, in contrast, are two rectangles which extend beyond the mandala’s eastern border or “threshold line” to the 1st enclosure’s outer walls and include whatever structures (shrines, crematoria, galleries) are inside it. Great ingenuity is applied to bring these two opposing geometric systems – and cosmic orders – into alignment, representing the asymmetrical, “out-of-joint,” chaos and continual flux of the profane world of illusion on the east and the symmetrical, precisely ordered, solidity of the square, - the “perfect form” in Hinduism - on the west. This produces a momentum in both the vertical and horizontal dimensions, a contraction and concentration along the “liturgical axis,” climaxing at the central shrine at the center of the mandala where all motion is frozen. Architectural and experiential space is further compressed as the worshipper approaches the smallest and highest terrace and then enters the still smaller shrine and finally the dark sanctuary or garbagriha, the primordial cave or “womb chamber,” in whose deepest recesses lurks the god, himself a manifestation of the seed, bindu, and dimensionless dot from which existence and extension and the universe emanate from the non-manifest, only to be sucked back at its destruction at the end of every mahayuga.

The darkness of the garbagriha at the end of the liturgical path is one way to express architecturally sunyata, emptiness, the “ground-of-non-being,” moksha and nirvana. Hindu temples could therefore be seen as paradoxically expressing their own ephemerality and lack of substance, their future dematerialization and disappearance, the “extinguishing” of all form and dimension. Does this account for the constant oscillation between emergence and contraction, between architectural prolixity articulating inner emptiness which sometimes makes Indian temples appear to jitter and pulsate? Could this be the ultimate architectural feat or sleight-of-hand, all the more impressive for reducing unprecedented masses of masonry to shimmering illusion? It provides a striking contrast with the expansiveness of Gothic vaults, Renaissance domes and Baroque quadratura (architectural trompe l’oeil,) as well as the measured, human-scaled spaces of a Greek temple or Palladian villa. The centripetal tropism and compression combined with mural decomposition into scintillating surfaces of Hindu sacred buildings is not uncommon in Islamic architecture where the liturgical axis or qibla draws the faithful from the external world through the sahn or avlu, the enclosed courtyard with its shadrivan or ablution fountain, before it enters the masjid or cami, the prayer hall, where it finally disappears in the infinite recess of the mihrab niche, stretching back to Mecca, the Kaaba in its shroud and finally Al Aswad, the Black Stone. Islam shares with Hinduism and Buddhism, an absolute, Allah, which like Brahman or sunyata can only be expressed apophatically and aniconically because it cannot be represented, imitated, named or conceived, “No vision can grasp him but his grasp is over all vision;” “He is the beginning and the end, the manifest and the hidden.” (Quran, 6:103; 57:3.) Allah, derives from the general Semitic term for a god, ilah, cf. Heb. Elohim, which means “the hidden.” Similarly, in Judaism God’s name cannot be written except with the elliptical tetragrammaton, Y*H*W*H. While in Islam this has taken the form of iconoclasm, a prohibition on representation of the created, parallel to the early aniconic linga of Saivism, in Hinduism and Buddhism it has had the opposite effect – an endless proliferation or avatars, bodhisattvas, yoginis, apsaras and erotic mithunas.

The asymmetry of the Khmer temple mountain could be attributed more pragmatically to an attempt to accommodate liturgical functions into an antipathetic symmetrical form – the pyramid, which, as already discussed led to the wide-spread adoption of asymmetrical, “linear expansion” in both Cambodian and Indian temple design, (see section III. “Linear Expansion: Phimai & Kandariya Mahadeva.”) At the same time that Suryavarman II (1113-1150) was building the pyramid of Angkor Wat, most of the other temples he constructed added mandapas and porches to the east of their shikharas, for example, Phimai, Banteay Samre and Thommanon, so the sanctuary or central shrine is also offset to the west of their enclosures. The extreme in asymmetry, however, is not found at Angkor’s temple mountains but at the mountain temple, Preah Vihear, on the border of Thailand, whose “processional path” stretches a kilometer before reaching its unassuming shikhara, beyond which is a sheer 2100 foot precipice; this might be seen as the most explicit and dramatic possible architectural expression of sunyata, the goal of Hindu and Buddhist, self-extinction, tumbling literally into the void of emptiness. (For a photographic survey of Preah Vihear's north-south axis, click here.) The overtly Mahayana Bayon raises the quest for symmetry to a higher level: not only does it draw its two rectangles of face towers into a square but then a circle, the perfect form in Buddhism, because emanating infinite, equal rays from an invisible bindu at is center. The last “temple mountain,” it rejects the square Khmer prasat for a unique, circular shikhara, radiating eight sub-shrines, but goes beyond this, by blurring the distinction between center and periphery, by dispersing point of view everywhere to evoke the spaciousness without direction or location of “Buddha consciousness.”