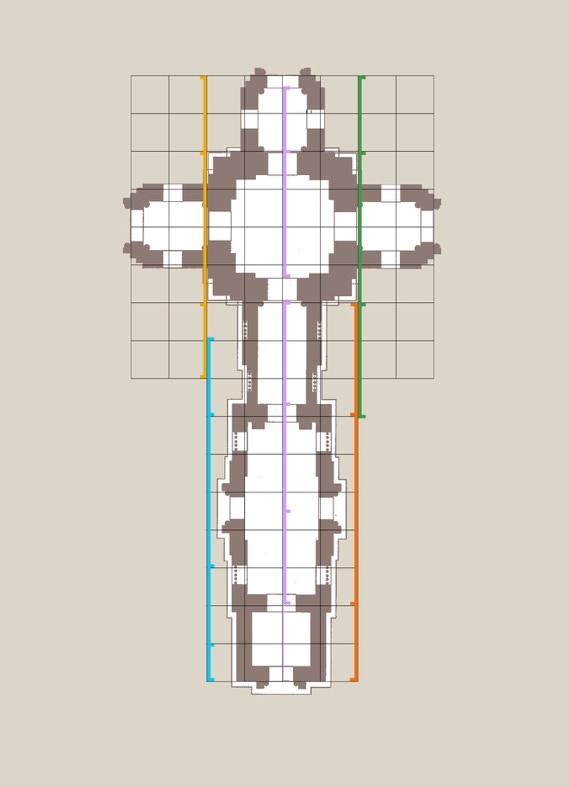

The shrine and its porches fit within a standard 8 x 8 manduka mandala (gray lines in figure 5) to which three additional structures are attached, also eight padas long but only two wide, doubling the temple’s length and establishing a directional, liturgical axis from south to north. First, the southern porch of the sanctuary is lengthened to form a narrow antarala, an “intermediate space,” antechamber or vestibule, linking the cella or garbagriha to a mandapa, an assembly hall or nave, 5-padas long (excluding its thresholds.) Finally, an ardhamandapa, a “half-open hall,” also mukhamandapa, “face” mandapa, adds an outer, southern porch or narthex, 2-padas square like the shrine’s north, east and west porches, but with just a single pediment showing Shiva Nataraja, “Lord of the Dance.” It is separated by a short path from the protruding northern arm of the 1st south cruciform gopura and gallery of the 1st enclosure, continuing the north-south liturgical axis from the 1st into the 2nd enclosures.

The chain of Phimai’s interrelated aedicules can be “read” as two symmetrical units: 1) the 8-pada square shrine with porches, itself divided into 2,4 and 2-pada units, (the tan bar at the top of figure 5) and 2) a 9-pada grouping consisting of the mandapa with two, 2-pada porches at either end divided into 2,5 and 2-pada units, counting part of the antarala as a notional, 2-pada porch, (turquoise bar) creating a 1-pada verlap between the two symmetrical groupings at the midpoint of the antarala. The temple’s “liturgical axis” can also be parsed as two asymmetrical groupings: 3) the

north porch, sanctuary and antarala, divided into 2, 4 and 3-pada units (green bar) and 4) the antarala, mandapa and porch, divided into 3, 5 and 2-pada units (orange bar at the bottom of figure 5.) The two groupings 3) and 4) oscillate depending on whether the antarala is read as attached to the shrine or the mandapa, similar to the resonance between the overlapping, symmetrical groupings 1) and 2.) A secondary motif provides counterpoint along the temple’s length (lavender line,) a 2⅔ pada unit equal to the length of a porch (with its inner threshold,) the interior of the sanctuary itself, the antarala and twice the length of the mandapa (measured here threshold to threshold.) These superimposed patterns tend to hold the separate or additive elements of the temple’s 16 padas in tension.

This sequence of aedicules at Phimai also presents a kind of dramaturgy for its “processional path,” crossing a series of thresholds before converging on the sanctuary where the formless absolute (the not so formless Buddha statue) waits. It stretches from the profane world of the town, which occupies the 3rd and outer enclosure at Phimai, across a naga or rainbow bridge, the usual Khmer symbol for the liquifying passage from solid earth to aethereal heaven, through the imposing 2nd south gopura, into the spacious 2nd enclosure and past a cruciform terrace with four ponds, representing the oceans separating Mt. Meru, home of the gods, from the home of humans. At this point, the long south gallery of the 1st enclosure fills the view and beyond it the temple’s shikhara or tower, symbol of Mt. Meru. The 1st south gopura, as deep as it is broad, next funnels the visitor into the 1st enclosure where the experience of space is very different, even cluttered. A path leads immediately to the south porch of the temple just a few feet ahead, hemmed in on either side by a laterite and a sandstone shrine. The modest ardhamandapa leads to two, north-pointing rectangles, the wider mandapa and narrower antarala which constricts further at the threshold to the sanctuary before finally opening out to the full, eight-pada wide, east-west cross-axis centered on the statue of Buddha. He is shown in dhyanamudra, meditating posture, during the sixth week after his enlightenment, when he announced, “Happy is he who no longer says, ‘I am.’” He sits beneath the seven-headed naga, Mukhalinda, who sheltered him from a rainstorm; the naga’s form is repeated by the antefixes of the tower directly above the statue. (Click here for eleven photos taken along Phimai’s south-north axis.)

The ultimate expression of Khmer “linear” or additive” expansion could be the mountain temple – as distinct from the “temple mountain”– such as Preah Vihear, Phnom Rung and Phnom Bakheng – where the metaphor of Mt. Meru and the “liturgical axis” up its slopes, include an actual mountain or hill. At Preah Vihear in the Dangrek range along the Thai border with Cambodia, for example, five enclosures and their gopuras mark a “processional path” a kilometer long, climbing a steep ridge or promontory, terminating in an anticlimactic shrine beyond which is a 650m sheer precipice. This rocky outcrop obviously provides no room to continue these gopuras into concentric, square galleries. (For an album of 15 photos documenting Preah Vihear’s north-south axis, click here.)

Phimai with the near four-way symmetry of its shrine, tower and four porches, followed by the two-way, east-west reflected symmetry of its southern extensions and three surrounding enclosures became the model for medium and smaller-sized Khmer temples during the subsequent reign of Suryavarman II (1113-1150,) including Thommanon, Banteay Samre, Wat Athvea and Chao Say Tevoda. Vaguely similar ensembles also crowd the inner enclosures of Jayavarman VII’s (1181-1220) Buddhist monastic foundations, Ta Prohm, Preah Khan and Banteay Kdei. “Linear addition” was also the favored method for axial extension at Indian temples, including such early shrines as the Upper Shivalaya Temple (c. 575) at Badami, the Meguti Jain temple at Aihole (632) and the Parashurameshwara Temple (c. 650) at Bhubaneshwar. The single cella of the Draupadi Ratha (c.650) was first extended by an open-sided porch with benches which then stretched into a mandapa’s hypostyle hall, providing the standard, linear ground plan for Hindu temples to the present. The evolution of “temple mountains” at both Angkor and Bagan demonstrate alternative strategies from those pursued so brilliantly at the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple for knitting an asymmetrical chain of aedicules into a temple’s larger fabric, specifically a pyramid symbolizing Mt. Meru.

FIGURE 5: ANALYSIS OF SITE PLAN, PHIMAI (c.1100)

PREAH VIHEAR FROM THE SOUTH, SHOWING THE 1st AND 2nd ENCLOSURES AND NORTH GALLERY OF THE TRUNCATED 3rd ENCLOSURE (11th Century)