NEAK PEAN (1181 - 1220)

NEAK PEAN (1181 - 1220)

ISLAND AND PRASAT, NEAK PEAN (1181 - 1220)

One of the most unusual monuments at Angkor is a small shrine on a round island in a square pool, surrounded by twelve other pools, all on an artificial island 300m on a side in the middle of the Jayatataka Baray. In other words, Neak Pean is a temple on an island on an island which is itself a "temple island," like East Mebon, West Mebon and Lolei, all monuments to a monarchs’ ancestor. Neak Pean is on the same axis as Preah Khan and, like it, dedicated to Avalokitesvara, the "bodhisattva of compassion" and posthumous deity associated with Jayavarman VII's father, Dharanindravarman II (1150-1160.) The shrine's Buddhist import was not lost on the Chinese chronicler, Zhou Duguan, who on a visit to Angkor in 1296 -1297, described Neak Pean, as "an island taking its charm from the ponds which surround it, cleaning the mud of sin from those who come in contact with it, serving as a boat to cross the ocean of existence,” the same metaphor for enlightenment realized in gravel and rock at Ryoan-ji, already referenced in connection with the land-locked Ta Som.

The shrine at the center of the temple is a typical, cruciform Khmer prasat with barely emerged double porches, double pediments and three blind doors, each with a standing figure of the tutelary bodhisattva, and a shikhara with two aedicular tiers crowned with a lotus blossom, not incidentally, the second metaphor for achieving satori through purification Zhou Duguan associated with Neak Pean. The shrine sits on a round island itself shaped like an open lotus pod with a lotus petal or padma molding around its base or jagati; with some imagination, the island might appear to float on water like one of Monet's Nymphéas. Between the two bands of lotuses, two nagas, their tails entwined, encircle the island, making the link between water, earth and heaven, all reflected on the surface of the pond, and intrinsic to the meaning of both the rainbow naga bridge and the lotus’ blooming. The two serpents form a kind of ouroboros or snake swallowing its tail, an symbol of immortality or, in an Indic context, cyclical temporality.

The central pool and its four tributary basins are thought to have represented the legendary Himalayan lake, Anavatapata, from which the four sacred rivers of India were said to flow, a symbol already encountered in the four pools in front of the 1st enclosures at Phimai, Phnom Rung and Muang Tam Hin and, perhaps, the four basins dividing the “cruciform cloister” of Angkor Wat’s 1st terrace. (The implications in Mahayana Buddhist of four issuing from one are discussed at the conclusion of the notes on Neak Pean’s site plan below.) The temple was, as Zhou Duguan observed, reputed not just to wash away the sins of pilgrims soul’s but to have medicinal powers for the afflictions of their bodies – hence, not just an island temple but a "temple spa." The central pool is surrounded by a terrace crossed by four small shrines at its cardinal points with statues of an elephant, horse, lion and human and a spout where pilgrims could douse themselves in lustral waters; (the one with a human head is visible in the photo above at left, the horse, at right.) These four subjects, perhaps coincidentally, are also included among the canonical sequence of six friezes around the half-walls of porches and mandapas of Hoysala temples such as Belur and Halebidu.

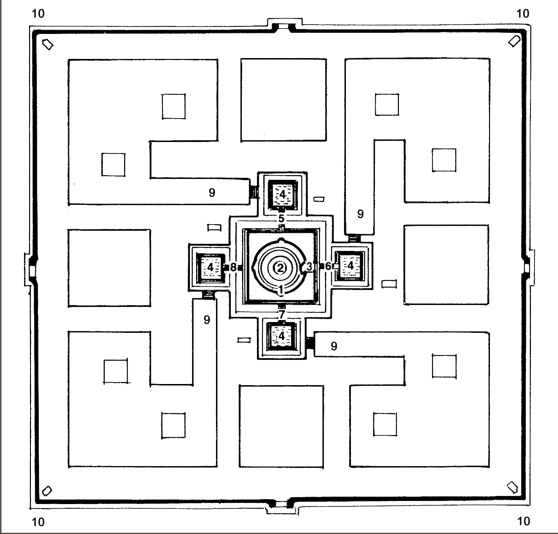

The most distinctive feature of the temple is the circular island on which the prasat rests because round shapes are so uncommon in Khmer and Hindu architecture where the square and orthogonal grid are regarded as expressing divine order. Buddhism, in contrast, privileges the circle, so it should come as no surprise that Neak Pean and the Bayon, both foundations of Jayavarman VII, attempt to interject radial elements inside a traditional rectilinear framework; (radial symmetry at the Bayon is discussed under figure 26C of the introduction.) The prasat or shrine’s square is reflected at many scales across the fabric of the temple, to such an extent, it forms a motif, almost a modulor or aedicule. As a result, seven concentric squares can be traced within the temple’s 300m square perimeter, as well as circles circumscribing all its major features. The right-facing angles of the J- or swastika-shaped pools (9) establish a repeated solar (clockwise) rotation sweeping around the temple.

It would be futile to speculate on the patterns, pedestrian or aquatic, used by visitors to the temple without a more precise knowledge of how it functioned, but it can at least be noted that Neak Pean’s plan seems designed to encourage, if not circumambulation, an indirect or circuitous, therapeutic and soteriological path towards its center. Borobudur in Java, analyzed in section V. "Borobudur: Mountain, Mandala, Monument" of the introduction to this catalog, and Neak Pean share what might be called an "architecture of diversion" with such notable Khmer temples as the Baphuon (1061) and Angkor Wat (1113-1150,) whose lateral (non-axial) galleries set up a similar rotational circulation. Neak Pean's frustration of axial motion is also consistent with a tendency noted in other of Jayavarman VII’s foundations – a de-emphasis or dissipation of the tropism or clinamen from the periphery to its isolated, perhaps inaccessible, center. Instead, it seems to sublate that dichotomy by revolving between its poles, balancing centripetal and centrifugal forces, in the continuous Buddhist interplay between emanation and occlusion, expansion and contraction. Another notable feature of Neak Pean is that wherever one turns, one encounters a reflection of the temple itself - in its pools inside islands and islands inside those pools. This might induce a sense of multiple centers and an confusion or interplay between inside and outside, somewhat similar to that already hypothesized for the “face towers” on the 3rd terrace of the Bayon. Here, however, the viewer does not disappear into the emptiness or awareness of sunyata inside the heads but a ceaseless, circular motion rather than a finite advance, where the “dancer becomes the dance.”

THE ISLAND IN DRY SEASON, NEAK PEAN (1181 - 1220)

SITE PLAN - NOTES TOWARD AN ANALYSIS

KEY TO SITE PLAN: NEAK PEAN

1 – Island with naga molding

2 – Central prasat with sanctuary

3 – Balaha statue

4 – Lustral basins (4)

5 – Elephant shrine

6 – Human (guru) shrine

7 – Lion shrine

8 – Horse shrine

9 – J-shaped pools (4)

SITE PLAN, NEAK PEAN (1181 - 1220)

BALAHA, CENTRAL POOL, NEAK PEAN (1181 - 1220)

The site plan above is based on thousands of aerial photographs but must still be regarded as highly tentative, since only the five inner pools have been drained, studied and restored. The outer eight pools and terraces around them remain vague, submerged outlines subject to a thousand years of erosion and sedimentation. It would be futile to attempt to assign a particular mandala across this temple since shifting water levels and the multiple moldings of its pools render the exact boundaries of any hypothetical padas highly conjectural. The dimensions on the site plan itself are inconsistent, presumably reflecting the vagaries of the data available to its draughtsman. Isomorphic and congruent structures can, nonetheless, be noted nearly everywhere at Neak Pean, even from this imperfect empirical evidence and from the admittedly circular but altogether reasonable assumption that this temple, like every other Khmer monument, was built around such symmetries and is unlikely to have so many purely by accident.

The following analysis describes only a few of the concentric squares and circles whose interaction suggests a radial motion around the temple. 1) Though the shrine (2) itself is square, its jagati (pitha, stereobate or platform,) the island (1,) is round. Since a square redented at an angle to its axes forms a stellate figure, approximating a circle as the number of its rathas increases, thereby “squaring the circle,” the island might be seen as the implicit radial projection of the redented square shrine, expressed by its circular amalaka or lotus crown. Similarly, the 300m square island will be found to contain a series of concentric circles. 2) The larger pool around this island bounded by the shrines, (5,6,7,8) returns to the square shape of the prasat at its center, so that this pool could be read as an “aedicule,” actually a projection and magnification, echoing the central shrine.

3) This larger pool, in turn, axially projects four smaller versions (or aedicules) of itself (4,) analogous to the porches of a shrine, except here they are fully-emerged, miniature square replicas; this group of five pools has the familiar triratha outline of a square with a superimposed equal-armed, Greek cross. 4) “Aedicular expansion” at Neak Pean takes the form of two-dimensional aqueous surfaces not three-dimensional stone volumes (unless one counts the basins’ hidden depths.) 5) This central ensemble of five squares, as already noted, is the section of the temple which has been accurately measured; it can be fitted roughly into the gridlines of a 9 x 9 paramasayika mandala where a) the smaller pools (with their surrounding edges) equals two padas each; b) the distance between them and the edge of the large central pool, constitutes one pada; c) the width of that pool, three padas, thus containing the nine central, Brahma-padas of the mandala; and, finally, d) the prasat itself occupying the central pada.

6) The outer corners of the four small pools can be circumscribed by a circle which includes the four lustral fountains. 7) If the small pools’ outer edges are extended to form the sides of a third, larger square, concentric with the central pool and prasat, the ratio of those three squares’ sides will be 9:3:1. 8) If this larger square is in turn circumscribed, that circle will be tangent to the midpoint of the inner edges of the four square, outer pools, projected along the cardinal axes. 9) A fourth concentric square can be formed by linking the inner edges of these outer pools with the inside corners them, of the four J-shaped pools (9) adjacent to them.

10) The outer corners of these same J-shaped pools (the areas where their two thick arms overlap) form four more squares, identical in size to the four outer, axial pools. 11) These eight squares are bisected by the cardinal and intercardinal axes and, thus, positioned like the guardian shrines at Ak Yom (700 - 725.) 12) The interstitial spaces between these eight squares are also squares, identical to them; together they form a border of sixteen squares, five per side, whose outside edges describe a fifth concentric square. (Their inside edges form the 4th concentric square, described in 9 above.)

NORTH APPROACH TO THE PRASAT FROM THE BARAY

On the east side of Neak Pean's central prasat, is an uncompleted statue of a horse rising from the sea with men clinging to its neck (unfortunately their heads have been looted) with dolphins breaching the surface to greet them. No trace of statues linked to the other figures in the shrines along the central square’s walkway – a lion, an elephant and a guru – have been found. This horse provides an example of the double appropriation of a Hindu myth by both Theravada and Mahayana Buddhist traditions. The statue itself represents a miraculous flying and talking horse in Hindu folklore, Balaha, who rescued shipwrecked Indian merchants (perhaps sailing to far-off Chenla or Funan) from Siren-like rakshashas or seductresses, similar to the type or topos, of Calypso, Dido, etc.

This folktale was given a Theravada interpretation in the Valahassa Jataka, one of the ”birth stories" from the Pali Canon, where Balaha becomes one of the 547 merit-earning, previous incarnations of Buddha (the 196th to be exact and the Jatakas are nothing if not exact.) In later Mahayana texts, Balaha, became an incarnation of Avalokitesvara, the “bodhisattva of compassion” of the present epoch, and, as has been pointed out, the dedicatee of Neak Pean and Preah Khan. In this telling, the horse rescued a merchant, Simhala, (presumably an eponym of the Indo-European ancestors of the Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka,) whereupon Simhala and his five hundred companions were converted to Buddhism, bringing those “teachings” to that island (albeit, in its Hinayana or “Lesser” form.)

The legend of Balaha resonates with two figures in Greek mythology who shared the same name though not species. The first Arion was a flying horse, like Pegasus, the offspring of Poseidon and Demeter, gods of the ocean and the earth, who rescued Adrastus, the sole Argive to survive the assault on Thebes. The second was a kitharode or lyre-player, who returning to Greece from a competition in Sicily, was kidnapped by pirates. Before being thrown into the sea, he asked a last request: to sing a hymn to Apollo, god of song. Even pirates dared not refuse such a boon and his dulcet tones summoned a school of dolphins who carried Arion safely to shore, presumably prefiguring the New Age enthusiasm for swimming with pods of dolphins.

13) The J-shaped pools contain eight square “islands-inside-an-island.” Were they just a place to swim or pedestals for statues (balipitha, socles,) for altars, like those in the western courtyards of the 1st enclosures at Preah Khan and Banteay Kdei? 14) These “islands’” innermost corners are equidistant from the center of the prasat and, thus, inscribe another circle which also passes through the inner corners (9, above) of the J-shaped pools. 15) The outermost or opposite corner of these eight square pedestals, fall on a circle tangent with the midpoint of the outer edges of the four axial pools and,hence,a fifth concentric circle. 16) Thus, these eight “islands-inside-an-island” ring the central shrine with emblems of itself.

17) The J-shaped pools suggest rotation like a windmill, cogwheel or swastika because the distance or radii between the right angles of both the four pools and their two islands and the prasat are repeated in each adjacent pool, like spokes radiating from a wheel’s axel. 18) The arms of these J-shaped pools are all right-facing angles, that is in a clockwise or solar direction. Although parikrama or ritual, solar circumambulation, is common in many Hindu and Buddhist traditions, there is no evidence that it was practiced at Angkor. Nonetheless, the direction of the sun is regarded as auspicious in many cultures, as implied by the etymology of swastika (Sans.> su good + asti it is + ka a thing.)

This ancient Vedic and Indo-Aryan symbol (explaining its attraction to the Nazis) had numerous connotations - good luck, change, the wheel of fortune, the chakra or “wheel of the law” and, of course the passage of a day or of a life. The shape is widespread in Celtic, Slavic, Chinese and Native American cultures, as well as, found combined in a continuous meander in Greek friezes, where it is called a tetra-gammadion because of its resemblance to the Greek letter gamma or a tetraskelion, meaning "four-legged."

A left-facing swastika or sauvastika is associated with death, mourning and ill-omen; thus, the murals at Angkor Wat, hypothesized to be a funerary temple, are usually viewed in a counterclockwise or apradakshina (widdershins) direction, that is, keeping them on the viewer's left. Tantra too, because of its sometimes transgressive practices, is often called "the left-handed path." Neak Pean may have been an ancestor temple but as a spa walking around it in an inauspicious direction would hardly have commended its healing powers.

The projection of four pools from one suggests the construction of a Mahayana or Vajrayana mandala for the five dhyani, wisdom or tathagata, Buddhas - Vairocana, Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amoghasiddi and Amitabha (of whom, Neak Pean's dedicatee, Avalokitesvara, is a manifestation.) To avoid any imputation of polytheism or duality, the last four are usually seen as manifestations of Vairocana, the central Buddha in the quincunx, and, as such, regarded as the Adi- or primal Buddha from which the others originate. In some Tantric sutras, a sixth, Buddha, Vajradhana, has been proposed, who is non-manifest (Sans.> nirguna, without attributes; niskala, formless, undifferentiated; or acintya beyond the mind's purview, the name of the chief deity of Balinese Hinduism.) He is the source of the other five, analogous to the dharmakaya, the immanent ”Buddha body,” (as opposed to the emanated, of which Sakyamuni was the historical embodiment). This can easily become an infinite regress, not to say digression.

73

74