TA PROHM (1186)

1

TA PROHM (1186)

1

This brief introduction to Ta Prohm (1186) will focus on features of Jayavarman VII's (1181-1220) first Buddhist complex which were more fully realized five years later at his nearby, even more ambitious foundation, Preah Khan (1191,) and subsequent temple monasteries. (That “horizontal temple mountain” is the subject of section XIII of the introduction and the next temple documented in this catalog.) The following photos and site plan demonstrate both the continuity of Jayavarman VII's temples with previous Khmer practice, as well as their notable disjunctions, a balance which that monarch seems to have tried to maintain when he introduced Mahayana Buddhism as the Empire's new religion.

Ta Prohm reaffirmed the venerable tradition, initiated by Indravarman I at Preah Ko (979,) generally regarded as the first temple of the Angkorian era, of constructing an "ancestor temple" as the first project of a Khmer king’s reign. It testifies to the devastation of the Civil War (1177 -1181) that it took an avid builder like Jayavarman VII five years to realize his first architectural endeavor. The temple was atypically dedicated to Jayavarman VII’s mother, rather than both parents, in her posthumous incarnation (technically, dis-incarnation or apotheosis) as Prajnaparamita, the twenty-two-armed Mahayana deity representing the "Perfection of Wisdom." In 1191, the king built an even larger monastery, Preah Khan, for his father, as a manifestation of Avalokitesvara (Kh. > Lokesvara,) the "Buddha of Compassion,” with whom he seems to have identified himself. Ta Prohm contained, as well, two smaller sub-shrines in its 3rd enclosure, the southern (8, on the site plan below,) consecrated to the king's personal spiritual advisor or guru who may have converted him to Buddhism, and the northern (9) in honor of his elder brother. The temple's inner three enclosures (6,10,12) were surrounded by an outer enclosure (1) 1km by 560m, which, according to its detailed dedicatory inscription, housed 12,640 resident monks and attendants and was endowed with 3,140 estates or villages with 79,365 bonded serfs to supply the complex's less than ascetic material needs.

STILL-LIFE: THE PARADOX OF PRESERVATION

Ta Prohm is the most picturesque temple at Angkor and accordingly among the most photographed as a result of an inspired decision by the relentless restorers of the EFEO to leave one temple as they found it. It has been meticulously preserved in what might be described as a "suspended state of nature,” staving off the tropics’ inexorable processes of decay and growth to achieve a carefully calibrated, artificial equilibrium, as any ecological steady-state must be. This allows today's visitors to share something of the frisson of the pioneering 19th Century archaeologists who stumbled on the still over-grown temple and then take a tuk tuk back to their comfortable hotels, pools and “happy hours,” after their brief foray into the pre-touristic past.

The two trees most responsible for chewing up Angkor's monuments are the cottonwood and appropriately named "strangler fig," which work their roots through fissures in the masonry down to the soil. While they crunch the temple, as in the example of the gallery pictured at right, they sometimes also hold their remnants together; when they die, however, the structure crumbles. Therefore the EFEO and now APSARA authority could not leave Ta Prohm to nature's questionable mercies but have had to clear unobtrusive, safe paths through the ruins and shore up sections in imminent danger of collapse with artificial supports (scrupulously marked CA for "Conservancy Angkor.”) These naga-like roots, which look as if they were transforming the temple's rock to bark, seem to confirm the Khmer view of all things in a process of metamorphosis, an ontological fluidity (or Heraclitean flux) they associated with shape-shifting water and, of course, the slithering naga itself.

The ravages of nature were abetted by certain Khmer building methods. Though obviously master masons and sculptors, they did not always observe current or even ancient "best practices" for making their monuments last (though it is only our self-interest which assumes preservation was one of their concerns.) For example, they used a natural resin to bind the blocks together rather than inorganic mortar, a "green" building technique avant la lettre. This natural glue decays like everything that lives and dies, opening spaces for invasive roots to enter while providing nourishment for their growth. In addition, the Khmer, unlike the Greeks, were not consistent in how they laid their stone courses; the seams or grain, the results of sedimentation, compress and harden if the ashlars are laid parallel to them but tend to splinter along these striations if laid vertically, as was too often the case at Angkor.

WESTERN GALLERY, 2ND ENCLOSURE, TA PROHM (1186)

EASTERN GALLERY, 3RD ENCLOSURE, TA PROHM (1186)

Finally, the Khmer, like the Hindu builders they may have emulated, used only corbelled vaulting, stacked stone slabs or bricks each projecting beyond the one beneath. They did not know the “Roman” or keystone arch which redirects tectonic forces to the walls and makes possible spanning such vast spaces as the Pantheon or Hagia Sophia. It has been argued, not without plausibility, that because the garbagriha was dark and small, Hindu sthapati did not need to cover wider spaces and therefore lacked the impetus to adopt the arch; (though this could also be adduced as a cause rather than effect.) It does explain why Khmer shikharas needed to be so tall and heavy and have suffered such a high casualty rate over the centuries. An alternative was available close to hand; the brick masons of Bagan’s 3500 pagodas, uniquely in South Asia, developed and employed a “true arch” for their monolithic gyus and zedis, perhaps an unintended benefit of working in an active seismic zone.

THE TEMPLE MONASTERY: A FIRST DRAFT

Ta Prohm may be the first example of what might be called a "horizontal temple mountain," (though Beng Mealea prefigures it in some respects,) where the vertical layering of stepped terraces of prior Khmer pyramids is replaced by a series of, concentric enclosures and symmetrical structures defining successive "virtual terraces." Here spiritual attainment would not be measured by ascent towards a peak or zenith but progress inward to a center, a dimensionless point of origin. Contrasting Angkor Wat with examples of this “alternative” temple plan, four tendencies can be distinguished: 1) decreased emphasis on axial direction and the diminished size and prominence of the central shrine (already noted at Beng Mealea c.1150;) 2) increased density of structures within the enclosures with a corresponding blurring of the boundaries between them; 3) a resulting multiplication of circulation patterns and tolerance for non-orthogonal, asymmetrical site design; 4) a "polycentric," “organic" or more “informal” relationship between the temple's parts, suggesting less a pre-existing plan than the gradual evolution of a network of nodes and neurons. Although these characteristics can be found in varying degrees in all Jayavarman VII's monastic foundations, they are described in greater detail using Preah Khan as an example, in section XIII, “Axial Diffusion, Confusion and Illusion.”

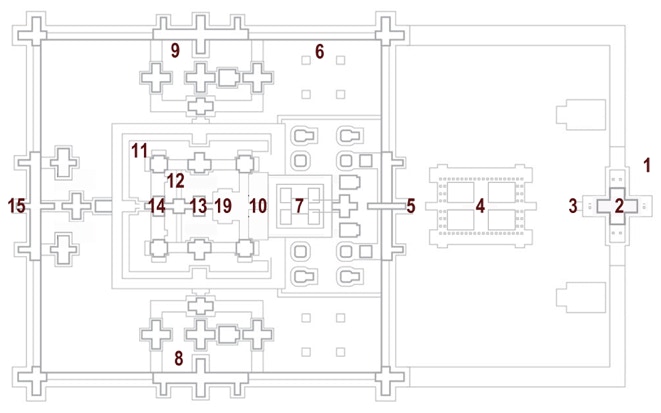

Key to Site Plan: Ta Prohm

1 – 5th enclosure

2 – 4th east gopura

3 – 4th enclosure and causeway

4 – “Hall of Dancers”

5 – 3rd east gopura and gallery

6 – 3rd enclosure

7 – “Cruciform cloister”

8 – South sub-shrine with “Great Departure Pediment”

9 – North or Prajnaparamita sub-shrine

10 – 2nd east gopura

11 – 2nd enclosure and peristyle

12 – 1st enclosure and gallery

13 – Central shrine and shikhara

14 – 1st west gopura

15 – 3rd west gopura and gallery

SITE PLAN, TA PROHM (1186)

This site plan and accompanying key maps only Ta Prohm’s inner three enclosures (6,11,12) and the eastern half of the 4th (3,) including the cruciform 4th east gopura (2,) the largest in the complex and a prominent feature of this class of temples. The 5th enclosure (1,) the small city where the priests and servants lived, lay beyond these four enclosures which together comprised only 1 hectare (2.47 acres) of the temple's 60 hectares (148 acres, where 100 hectares = 1 sq. km.) A broad causeway (3) leads across a moat past an open-sided, octostyle (eight pillar wide) hall (4) in the same position as the naga terraces at Preah Khan and Banteay Kdei, and analogous to the cruciform terraces in the 4th enclosures of the Baphuon and Angkor Wat. (At Preah Khan and Banteay Kdei similar structures appear on the same axis but inside the 3rd enclosure where they are commonly called "Halls of Dancers," (by analogy, one suspects, with the open-sided rangamandapas of Hindu temples, stages for public performances and sacred dances, of which the most famous is the nata mandir at the 13th Century Surya Temple at Konark. In Indian practice, these were usually separated from an enclosed gudhamandapa adjacent to the garbagriha, reserved for worshippers who had been adequately prepared to face the god himself.) From the “Hall of Dancers” the axis proceeds to the 3rd east gopura (5) and the outward-facing dipteral peristyle of the 3rd enclosure (6.) The site plan makes clear the privileging of the east-west, "liturgical" axis; Ta Prohm is the first Khmer temple where the 3rd east (5) and 3rd west (15) gopuras are linked in an unbroken enfilade of structures – lacking even the ambiguous aqueous passages at Banteay Samre and the sole gap west of the shrine at Beng Mealea.

This allows an unobstructed view across the temple’s breadth, a rhythmic series of thresholds among which the central shrine becomes almost indistinguishable. At Ta Prohm, the crucial new link is provided by "linearly-expanding" the sanctuary (13) not just to its east but also to its west by inserting a square, enclosed hall between the cella's western porch and the eastern and only porch of the cruciform 1st west gopura, a structure without precedent in Khmer architecture. On the sanctuary’s east, its eastern porch connects without an antarala directly to a semi-open hypostyle mandapa or congregational hall, broader than it is long with north and south porches, which abuts without an ardhamandapa (eastern porch) the 1st east gopura.

We cannot know how the function of the central shrine or sanctuary may have changed at Angkor when it was no longer inhabited by a “wakened” Hindu deity who could deliver auspicious darshan but, instead, by a statue of Buddha, an icon or marker of his absence because his ultimate achievement was his non-existence. We might expect that the switch from the populous, polytheistic Hindu pantheon not just to a monotheistic but atheistic religion would lead to a radical reduction in the number of shrines. One consequence of the change to an apophatic (invisible, inconceivable, non-manifest) absolute seems to have been the proliferation of an infinite number of its emanations, albeit illusions or maya, allowing Ta Prohm to be dedicated to no fewer than 216 bodhisattvas.

At Ta Prohm direct access to the shrine itself from the liturgically privileged eastern approach is restricted to the central axis. The three parallel corridors leading directly from the 3rd east gopura to the1st enclosure at Beng Mealea and Preah Khan are not found here. Angkor Wat’s "cruciform cloister" (7) has been awkwardly squeezed against the eastern wall of the 2nd enclosure (11,) while neither north or south galleries of its 1st or innermost enclosure (12) connect directly with this somewhat gratuitous cloister, just as its own three galleries do not extend to the gallery of the 3rd enclosure (6.)

The tendency towards diminishing the role of the 2nd enclosure (11,) noted at Beng Mealea, results at Ta Prohm in its reduction to an inward-facing dipteral peristyle opening onto the blind baluster windows and cruciform corner towers of the 1st enclosure (12.) It has even been deprived of its own gopuras, afforded merely a widening at the cardinal axes where it “leaks” into the 1st gopuras. On its east, the 2nd enclosure’s colonnade dissolves into a narthex leading to an incoherent grouping of more than twenty small shrines or chambers between it and the gallery of the 1st enclosure, interrupting any axial momentum and blurring the distinction between the two enclosures. The contiguous "cruciform cloister" (7) and the ancillary shrines scattered around it in the 3rd enclosure (6) tend to merge all three enclosures on their east into a dense conglomeration with no organizing principle but addition.

This impression is aggravated by the scattering of discrete structures, each with its own competing symmetry, around the periphery of the 3rd enclosure – an "aedicular proliferation" and “dispersion” not seen since the more orderly array of shrines at Phnom Bakheng (907.) The ten loosely related shrines on the east of Ta Prohm's 3rd enclosure's (6) lack a unifying plinth as at Prasat Kravan or Koh Ker and obscure the view of the 2nd enclosure. The hypostyle hall in its southeast corner may be related to the shrines hypothesized for the same position at Beng Mealea. The south and north shrines (8,9) for Jayavarman VII's guru and brother are designed as temples in their own right: a surrounding gallery with the familiar east-west linear expansion: an eastern gopura > a errace/ bridge > an ardhamandapa > a maha- or gudhamandapa > an eastern porch/ antarala > the garbaghriha > its west porch > a gap > the western gopura. Their three parallel corridors and crossbars or transepts seem to have provided prototypes for the three peripheral shrines at Preah Khan, except here access to their sanctuaries is not from the liturgically correct but adrift eastern gopuras but the larger northern, western or southern one they share with the 3rd enclosure (6) and, on their inner sides, the northern, western or southern axial arms connecting the sub-temples through the 2nd (11)and 1st (12) gopuras and enclosures to the central shrine (13.)

PORCH, NW CORNER, 1ST ENCLOSURE, TA PROHM (1186)

COLONNADE, 2ND ENCLOSURE, TA PROHM (1186)

3RD WEST GOPURA, TA PROHM (1186)

The ruined state of Ta Prohm makes the more convenient entrance for visitors today from the west, although, like most Khmer temples, the liturgical axis stretches from the 4th east gopura. The 3rd west gopura and gallery (15) pictured here are in almost all respects duplicates of the ones on the east: an outward-facing, double colonnade in front of blind, baluster windows. The gallery surrounding the 3rd enclosure (6) has a split shala or valabhi profile, a barrel-vaulted roof with an aedicular, half-story and eave over the outward-facing dipteral colonnade. The roof “steps” forward and down in three stages or “staggers” from the central tower, a standard Khmer prasat module with porch and dormer, the equivalent of a Dravida panjara aedicule whose nasi or kudu, has been replaced by a Khmer double torana arch and pediment. The uppermost roof covers the cruciform central chamber, the second its laterally projected or “telescoped” porch and the third its cruciform north and south pavilions. The modest naga bridge in the foreground connects with the 4th west gopura across the moat. Inside the 3rd enclosure (6,) just beyond this gopura, in place of the agglomeration of shrines and cloister (7) on the east, are two small, cruciform shrines and a single Khmer prasat with four porches athwart the east-west axis connecting the 3rd (15) with the 2nd west gopura.

ICON AND ICONOCLASM

The central figure on this pediment and his disciples on either side have been defaced and so can confidently be identified as victims of the brief brahmanic or "Hindu fundamentalist" reaction under Jayavarman VIII (1245-1295,) which systematically erased every Buddhist reference from the monuments of that king’s more eminent predecessor, Jayavarman VII (1181-1220.) All that remains here is one leg dangling from the gouged-out niche in which a Buddha presumably sat; since Mahayana Buddhism was favored by that monarch, it could have been any of the five dhyani or tathagata ("wisdom") Buddhas. The pose is known as "royal ease" in recognition of Buddha's royal birth and spiritual attainments. His hands might have been in vitarka or teaching mudra explicating a point of dharma to his followers. The remainder of the pediment did not seem worthy of redaction, most likely because the disciples beside the Buddha and in the lower register are depicted in the same manner the Khmer used for followers, sages or rishis of the Hindu gods, especially Shiva. The two small trees on the right and left of the second register probably allude to the sala trees under which Buddha was said to have been born and died or the bodhi fig tree (ficus religiosa) where he achieved enlightenment. But the Khmer convention of using a single tree to represent a forest allowed them also to be applyined to a range of Hindu subject matter, for example, Mt. Kailasa, populated by Shiva and his hermit followers, or the Dandaka forest where Rama was exiled and lost Sita.

DEFACED BUDDHIST PEDIMENT, TA PROHM (1186)

The frequently reproduced pediment below is from the eastern entrance to the sanctuary of the southern shrine (8,) dedicated to Jayavarman VII's Buddhist guru. It shows one of the central scenes from Buddha's life, "The Great Departure," when Prince Siddhartha Gautama, (also known as, Sakyamuni or "the Sage of the Sakyas," his clan name,) at age 29 renounced his former life as a prince of Kapilavastu in present-day Nepal to begin his quest as an ascetic, sramana or wandering truth-seeker in search of satori, awakening or enlightenment, which required detaching himself from the samsaric entanglements binding him to the illusions of quotidian life. Since Siddhartha knew those attachments, in the form of his father, wife, son and subjects, would resist his decision, he left under cover of darkness with just his horse, Kanthaka, and groom, Channa, (and, in this depiction, servants carry royal parasols and flywhisks of honor.) The gods placed the women of the palace in a deep slumber and, to ensure the guards would not hear the horse's hoofs, lifted it off the ground. The horse would die of grief over its master's abandonment, while Channa would become a disciple and arhat or enlightened being. Prince Siddhartha Gautama would, of course, become the Sakyamuni Buddha, 28th in a line of bodhisattvas who delayed their entry into nirvana or non-being to teach suffering humanity the secret of salvation from the pain of loss which they equated with living.

"THE GREAT DEPARTURE PEDIMENT," SOUTHERN SHRINE, 3RD ENCLOSURE, TA PROHM (1186).

This subject is especially appropriate for the shrine of the king’s guru since it could symbolize both Jayavarman VII’s departure from his role as a Hindu chakravartin to that of a Buddhist leader like Asoka, as well as embarking on the spiritual path of that faith in the footsteps of his trusted advisor. This does not seem to have inconvenienced the king from consolidating and expanding the Khmer empire and undertaking one of the most ambitious building campaigns in history. During the last twenty years of Jayavarman VII’s reign, however, the epigraphic record becomes uncharacteristically silent which has usually and plausibly been attributed both to his advanced age, (he was born sometime after 1120 and died in 1220,) when he might have chosen to lead the more cloistered life of the fourth stage or ashrama of Hindu life, Sannyana, or renunciation of the world, perhaps in this very temple monastery.

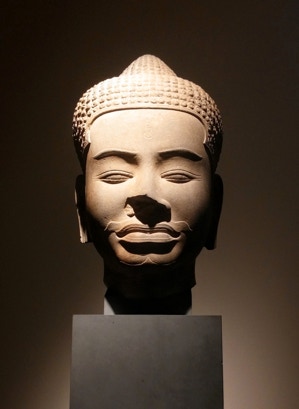

This bust somehow escaped the hammers of Jayavarman VIII (1243-1295,) the Narendra Modi of his day, and his Bharatiya Janata Yuva Morcha thugs, perhaps because it postdates his reign and was carved during the Theravada Buddhist ascendancy of the 14th Century. The chip to the nose does not detract from the sense of poise and inner absorption, which makes it an image of equanimity. The bust is clearly linked to the historical Buddha by its display of some of the tell-tale mahapurusa laksana, "the thirty-two marks of a great man," with which he is always depicted. These include: the identical curls of his hair, the urna or whorl in the middle of his forehead, symbolizing the "third eye" of divine vision, (a Buddhist appropriation of the bindu, the dot worn by orthodox Hindus marking Shiva’s third eye,) and his ushnisha or "fleshy cranial protuberance" from which the flame of enlightenment can be discerned "by those with eyes to see."

The ruins of Ta Prohm can be read as more than testimony to the Khmer Empire’s glory and centuries-long oblivion. They are among the most conspicuous memento mori on earth, icons of the absent past, perpetually mocking the apparent permanence of the present and the hubris of those who wield power over it – for just a minute. Their vanity was immortalized by Shelley's iconoclastic, toppled statue of a pharaonic tyrant, Ramasses II, whose epitaph read: "My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings./ Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair." The film director, Federico Fellini, recounted that he was inspired by another famous ruin to make his Satyricon (1969,) based on Petronius’ picaresque novel of Roman decadence written c.60 C.E. One night driving past the Colosseum, its hulk struck the director as a gigantic skull in the middle of the modern city; the thoughts and passions of the thousands who had cheered, flirted and suffered there, turned to wind through its crumbled arches, as would the life teeming around him on that torrid, summer evening. The “Eternal City” also served as an emblem of transience for Wallace Stevens in his 1952 tribute to George Santayana, "To An Old Philosopher in Rome.” Like some visitors to Ta Prohm, he found in its rubble:

…“the afflatus of ruin,

Profound poetry of the poor and the dead,

As the last drop of the deepest blood,

Falls from the heart and lies there to be seen,

Even as the blood of an empire it might be."

Like Keats' Grecian urn, Angkor speaks not just through its monuments but their silence, not just through the questions we ask but the voices who do not answer.

BUST OF BUDDHA, FOUND AT TA PROHM, MUSEE GUIMET

(13TH OR 14TH CENTURY)

COLLAPSED SHIKHARA, 1ST ENCLOSURE,

TA PROHM (1186)

68

74