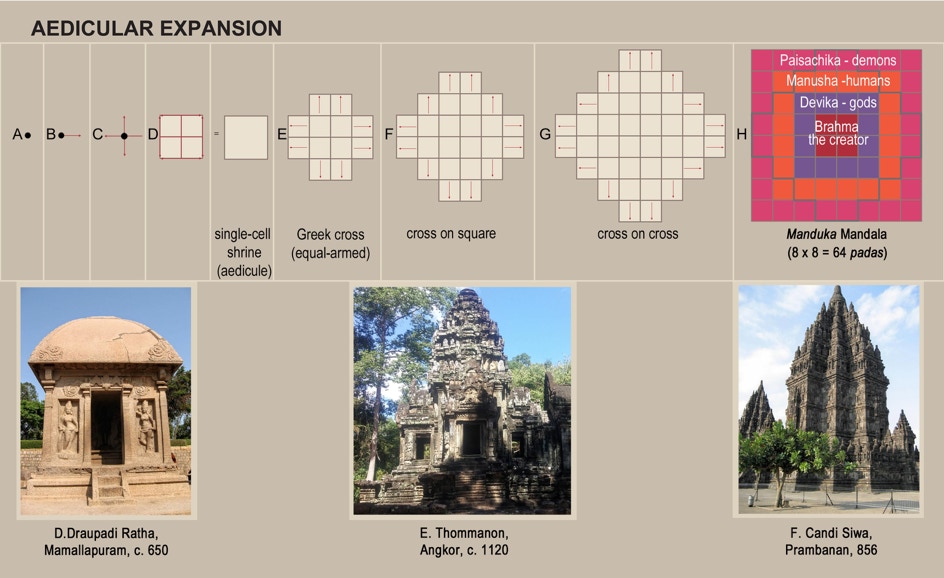

FIGURE 3 A - F: GENERATION OF AN 8 x 8 PADA MANDUKA MANDALA FROM A POINT

Reckoning with Rathas

The terminology for Indian temple architecture can often be confusing because of the different traditions which have developed across the subcontinent; they are, however, essential for referring to the parts of these highly detailed building.

Ratha, for example, has two distinct meanings in Hindu architecture: 1) the chariot of a god carried in a procession or a replica as a fixed part of a temple, e.g. the jagamohana of the Surya (Sun) Temple at Konark, Odisha (Orissa;) 2) a vertical projection, (angle, facet, offset, redent, ressaut or result) tangent to a notional circle circumscribing a square core, (shrine, prasat, prasada, cella, garbagriha, shikhara, rekha deul, vimana;) rathas may also be called pagas or latas in the Nagara tradition. Both vimana and prasada can also have the same double meaning as rather.

Rathas, in this second sense, may be orthogonal (at right angles to the vertical and horizontal axes) resulting in cruciform, staggered or stepped outlines, or rotated at an angle to those axes, producing stellate shapes. The most common plans have 3, 5, 7 and 9 projections referred to by their Sanskrit names: triratha, pancharatha, saptaratha and navaratha, but some stellate forms have as many as 24, 32 and 48 rathas, for example the Doddabasappa Temple at Dambal in Karnataka with 24.

The number of rathas is conventionally counted between the diagonals of the square core from which the rathas project, (not from between its cardinal axes;) only one diagonal corner per quadrant is counted, so the number of rathas is always odd. The standard Khmer shrine module, for example, is pancharatha, with five rathas: a central square with two broad but barely-emerged (shallow, slightly-projecting) crosses superimposed on it. Portals (jambs, colonettes, pilasters,) may or may not be included as rathas; the indentations of the varandika (cornice) or jagati (stylobate, base molding) can provide an indication of their number.

In a pancharatha shrine,the outer, corner or first ratha ( is called the kanika, konaka or karna ratha; the two intermediate rathas (2 and 5,) the anuraha or anardha rathas, while the two central rathas (3 and 4,) the raha rathas or bhadra. In saptaratha shrines, the rathas, (2 and 7,) adjacent to the corner or kanika rathas can be called pratirathas, as the rathas (4 and 5) adjacent to the the central strip, the bhadra or raha rathas, are sometimes called lata rathas. All these terms are subject to local usage.

A vastu purusha manduka (8 x 8-pada) or paramasayika (9 x 9-pada) mandala can be generated from a point, as in figure 3, by projecting a line in one direction from the primal dot or bindu, creating the first dimension, then three more in the other cardinal directions, creating an x- and y-axis, a plane and a second dimension. If each of these four lines then projects a line laterally on either side of it, (that is, at right angles to itself,) at equal distances from the axial crossing, they will form four squares or a single larger square whose center is the axial crossing; It appears that the earliest Hindu shrines were square wattle or mud brick huts with curved thatched or bent bamboo roofs. A model of this type has been preserved, the Draupadi Ratha, figure 3D above, carved from a solid granite outcrop at Mamallapuram (formerly Mahabalipuram) on the Coromandel Coast of Tamil Nadu near Chennai (formerly Madras,) one of five monolithic temple “prototypes” or rathas at this site. These early shrines are also thought to be recalled in the rounded roofs of the chaitya halls of early Buddhist cave temples, such as those at Ajanta in Maharashtra near Mumbai (formerly Bombay.) A square shrine or cella with a roof gathered at the center like a “cap” placed on top of solid walls or pillars constitutes a Dravida or Southern Indian alpa vimana or kuta, one of the most common shrine “types” in Hindu architecture.

Continuing the dynamic of “aedicular expansion,” each of these four squares projects one additional square along each axis to form a Greek or equal-armed cross with eight squares. The four central padas constitute the garbagriha, “womb chamber’, sanctuary or cella, while the added eight form four, 2-pada porches. Since the square module or aedicule from which they emerge is 2 x 2 padas and since they are only 2 x 1 padas, they have emerged only partially, half-way or 50% of their width. The sanctuary and its four porches of Thommanon, figure 3E, a small temple built just before Angkor Wat, approximate a Greek cross. Projecting one more aedicule, not just axially but laterally results in a central square with four rows of four padas each with a superimposed, equal-armed cross, two padas wide and six padas long, producing a staggered or redented, triratha outline, with three rathas or angles in each quadrant. A very large example of a triratha shrine would be Candi Siwa, figure 3F, a Saivite complex at Prambanan in southern Java (c. 850 C.E.,) a date when it could have influenced the earliest temples at Angkor. Adding another square to those above, results in two rectangles, 4 x 6 padas at right angles to each other forming a broad cross on which a narrower, equal-armed cross, 8 x 2 padas is superimposed, as in figure 3G. This can then be expanded laterally to form a manduka mandala of 8 x 8 squares or padas, composed of four concentric squares of 4, 12, 20 and 28 padas around their edges, figure 3H.

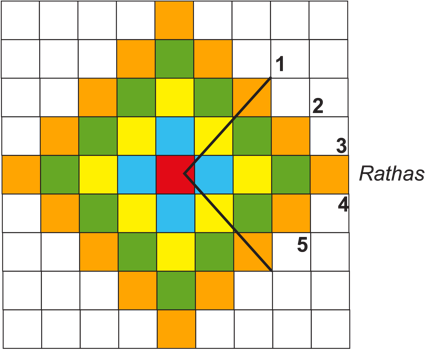

A paramasayika mandala is employed almost as frequently as a manduka; it begins from a single square (red in the diagram below, cf. figure 3D) rather than a point, which emanates four squares or porches (blue) forming an equal-armed Greek cross three padas wide. Following the process of aedicular expansion, it adds green, yellow and oranges squares resulting in concentric crosses 3, 5, 7, and 9 padas wide, containing 5, 13, 25, and 41 padas respectively. The last consists of one cross 9 x 1 padas long, superimposed on another cross, 3 x 7 padas long, both superimposed on a 5 x 5-pada square, resulting in a pancharatha shrine, that is, with five rathas (numbered on the diagram,) the most common Khmer shrine. This cross’ forty-one padas can then be expanded into a 9 x 9-pada square with 81 padas, a paramasayiika mandala, consisting of five concentric squares of 1, 8, 16, 24, and 32 padas. Indian architects discovered they could increase the number of facets by using overlapping aedicules, that is, aedicules only partially emerged, ⅛, ¼ and ½ their width (see figure 3E and figure 8.)

It should be noted here that the Khmer throughout their nearly 500 year floruit employed essentially the same “aedicule,” actually a L. > “aedes” or building, the ubiquitous pancharatha (with five rathas) prasat Sans. > castle, palace, temple > Sans. prasada, dwelling, residence (of a god,) temple. This consisted of a garbagriiha, the shrine, sanctuary or cella, with a shikhara, tower or superstructure, of four compressed tiers, each repeating the outline of the shrine beneath it; these qualify as the only strictly defined aedicules used in Khmer architecture. This “aedicule, in the larger sense, was then cloned and projected at unprecedented dimensions. Viewed strictly from the perspective of “aedicular expansion,” the pre-eminent Khmer monument, Angkor Wat, might be described as three, immense, identical tiers or talas, (its terraces,) each with eight identical prasats or “aedicules,” (its towers,) linked by endless harantaras, (its galleries) with the garbagriha or cella,not underneath the talas, but at their tip like a giant stupi. This reductio ad absurdum results from reading one “architectural language” in terms of another, a danger given the lack of a Khmer building lexicon.

Paramasayika Mandala

9 x 9 = 81 Pada Grid