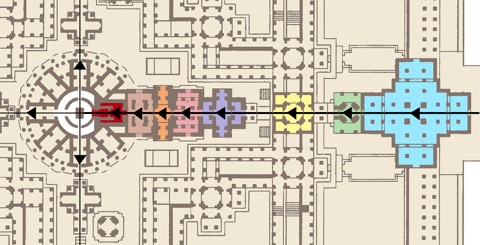

A Varjrayana “Anti-Architecture?”

The “liturgical path” between the Bayon’s outer or 2nd east gopura (shaded

turquoise in figure 24,) and the central shrine and tower (white) contrasts markedly

with Angkor Wat’s (see figure 17.) First, its distance is greatly compressed into

an interlinked sequence of small chambers, while, at the same time, the number of

thresholds (marked on figure 24 by black arrows) and shrines it crosses along this axis is

greatly increased. Second, these structures are enclosed, often in doubled “rooms-inside-rooms,”

in contrast with the open 1st terrace, its cruciform cloister, the 2nd terrace’s “cruciform walkway”

and the colonnades and pavilions of the 3rd terrace of Angkor Wat. At the Bayon, as soon as, the east-west, “liturgical axis” passes through 1) the spacious east gopura (turquoise) of the 1st gallery and its inner porch, it narrows to 2) a small vestibule (green) beneath the seventh axially-projected face tower, which contains an octagonal shrine or altar, the first of seven such enclosed spaces, unlike any others found in Khmer architecture. Like the six other face towers on the “liturgical path,” this one is hidden from view because directly overhead. After passing over a small “bridge” to the middle face tower of the 1st east triple gopura, the axis enters 3) a square room (yellow) blocking the inner and outer colonnades of the 2nd gallery and surrounding a second room or shrine, further sequestered from outside view. Most visitors, however, would file through the outer or lateral, two 1st east gopuras, be diverted up two flanking flights of stairs and shunted down a passage, almost too narrow to squeeze through, barring their view of the linked structures on the central “liturgical path,” until they emerged onto the open 3rd terrace surrounded by face towers. Those, however, privileged to pass along the "liturgical axis" (black line with arrows) would next find themselves in 4) another double shrine (lavender) shielded on all four sides by two lateral porches and two axial vestibules, which, in turn, gave onto 5) a slightly larger room (rose) comprised of a nave four columns wide, recognizable as a mandapa by both its lay-out and position on the axis relative to the shrine, but far too small to hold more than a few initiates, priests and perhaps attendants. Two partitions project into this room funneling directly into 6) a narrow three-chamber-wide space (tangerine) with a cruciform shrine at its center, similar to 4 except without its vestibules. It connected with 7) a larger rectangular room (tan) with a partitioned platform at its center, perhaps

another altar. This was followed by 8) another

windowless “room-inside-a-room” (crimson,) built in

the space once occupied by the original eastern

porch of the cruciform central shrine, whose rear or

western wall blocks the dead-end ambulatory around

the present cella. A narrow chute penetrates this wall, by

far the smallest space on the entire eastern corridor,

with room for no more than one or two people.

This further narrows at the threshold to 10) the

diminutive circular cella (white) where the Buddha

statue would finally become visible. (In 1933, a

Buddha seated under a naga marking the

sixth week after his enlightenment, similar to the

one at Phimai, was discovered shattered at the foot

of a cistern beneath this shrine, presumably a victim

of Jayavarman VIII’s Hindu fundamentalist iconoclasm.

Reassembled, it is now housed in a shrine behind the

twelve Prasat Suor Prat towers not far from the Bayon.)

This cella or sanctum sanctorum is encircled by the blind ambulatory (also white) which gives access to the 3rd terrace through the north, west and south sub-shrines or porches.

What can be inferred from this sequence of claustrophobic, conjoint rooms? First, that only one or two people at a time, perhaps the monarch, his guru or priest, not a procession or royal retinue, could participate in the rituals for which they were intended, presumably as preparation to behold the Buddha image and the terrace beyond. Second, these rites, whatever they may have been, seem to have been intentionally screened from the view of the laity or less enlightened, not just those on the 3rd terrace's open podium but even the chosen few in the adjoining antechambers, (somewhat reminiscent of the transubstantiation of the Eucharist behind an iconostasis in the pre-Tridentine church.) Finally, whoever passed along this liturgical path would have his sight restricted, even deprived, in a kind of optical austerity or asceticism, by both the prevailing gloom and the narrowing spaces, focusing his vision to behold (or visualize) the cult image, while making the revelation of the face towers all the more overwhelming. The complex and clandestine design of the Bayon’s liturgical path from its 2nd (outer) enclosure to the cella is consistent with its use for occult, perhaps transgressive, Tantric practices (and their negative perception by the more orthodox unintiated.) As noted, the secretive nature of these rites makes finding concrete evidence or explicit reference to them in the necessarily public epigraphic record unlikely. This can neither be adduced to affirm or deny the presence or influence of Vajrayana Buddhism at the Bayon and court of Jayavarman VII, only to explain why central facts about the site's liturgical use may always elude its investigators. Moreover, the highly unusual sequence of rooms, outlined in figure 24, proves only that occult, Tantric rituals could have been performed at the temple, not that they were.

HEAD OF BUDDAH, BAYON, MUSEE GUIMET (1181 - 1220)

FIGURE 24: “LITURGICAL PATH” FROM THE EASTERN GOPURA OF THE 1ST GALLERY TO THE CELLA,

BAYON (1181-1220.)

FOR A KEY TO THE SHADED AREAS PLEASE SEE TEXT ABOVE AND TO THE LEFT