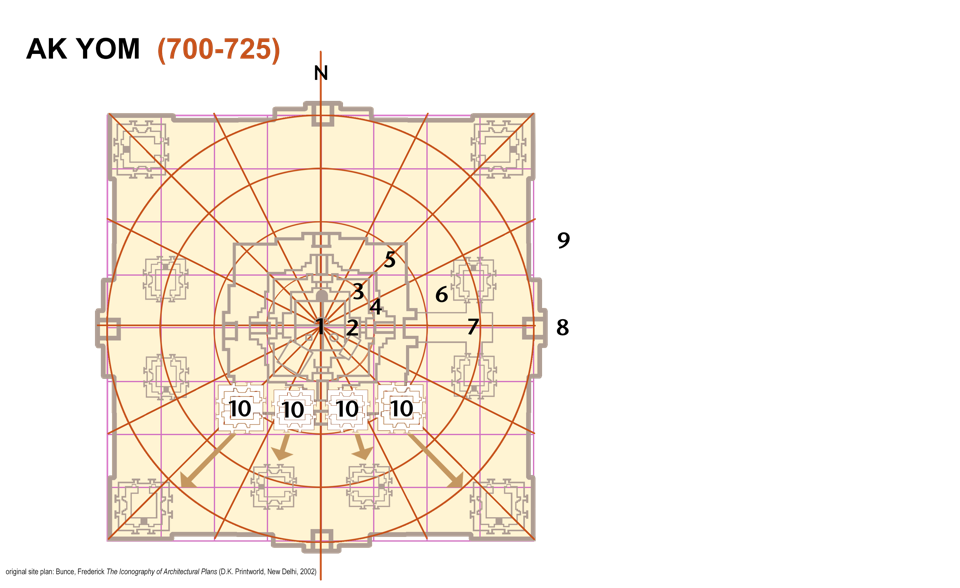

FIGURE 12:

ANALYSIS OF SITE PLAN, AK YOM (700-725)

1 Linga

2 Sanctuary, garbagriha

3 Shrine, prasat

4 Eastern entrance to the shrine

5 Plinth, 3rd terrace (1st enclosure)

6 2nd Terrace (2nd enclosure)

7 “Cruciform walkway”

8 Eastern entrance to 2nd enclosure

9 3rd enclosure

10 Four retracted southern shrines

The temple’s 100m sq. 3rd or outer enclosure (9) has never been fully excavated but a reconstruction of its 2nd and 3rd terraces (5, 6) is consistent with a sixty-four-pada manduka mandala (lavender grid.) The square shrine (4) has four protruding portals with nine, barely emerged projections per quadrant, hence navaratha.These are very shallow and mural, more applied pilasters and frontons than clearly articulated porches or aedicules, another example of the Khmer resistance to elaboration, in favor of replication of the basic square of their prasat module. The square shrine surrounds a square sanctuary or garbagriha (2) with a Shiva linga (1) and occupies the four central or Brahma padas of the manduka mandala, as prescribed in the Vastu Shastra. Its narrow plinth, with five barely suggested rathas (5,) completes the 1st terrace which fits comfortably within the twelve surrounding devika padas. In place of emergent or additive aedicules, ten free-standing, smaller versions of the prasat or “detached aedicules” have been projected around the 2nd enclosure in the cardinal and intercardinal directions. This is consistent with a role as Guardian Kings, directional deities who protect the slopes of Mt. Meru or Sumeru from defilement by the mortals and lesser beasts who skulk around its base, (see appendix V, “The Directional Guardians.”) In Buddhism, these guardians became transformed into avatars of the fierce Tantric bodhisattva, Vajrapani. The six, smaller, facing shrines act as dvarapalas or “door guardians” flanking the shrine’s portals; here, however, they have “stepped out of” their usual niches on the shrine’s walls, while preserving a space for worshippers to pass between them. If these six small shrines and the four larger corner aedicules (and the two small missing shrines on the north) were retracted around the central shrine, rather than projected away from it, they would exactly fill the devika padas corresponding to them, as shown in the diagram for the two southern pairs (10.) The projection of the four larger corner shrines in the intercardinal directions reappears on a much larger scale in the chiastic (x-shaped) panchayatana or quincunx arrangement of four shrines with a fifth at the center found on the upper terraces of Phnom Bakheng, Pre Rup, Ta Keo and Angkor Wat among others.

A “cruciform walkway” (7) connects the two eastern, facing shrines with the 3rd, upper terrace or plinth (5) while an “implied” fourth arm would extend to the primary, eastern entrance of the 2nd enclosure (8.) This suggests the “cruciform walkways” which will feature at later Khmer temples, notably, the two on the east and west of the 1st terrace of the Baphuon and the one on the 2nd terrace of Angkor Wat, where they appear to denote thresholds along the “liturgical axis” to the central shrine and cult image, (here the linga (1,) Shiva’s aniconic symbol, within the sanctuary or garbagriha.) The temple precinct also fits within a superimposed circular manduka mandala (orange circles) with four concentric rings one pada apart, which can be further subdivided into sixteen equal sections by the cardinal axes, the intercardinal diagonals and lines bisecting these eight angles. The latter position the corners of the six smaller, facing shrines, as similar implicit lines will be used to align the projected parts of the more complex temples of the coming centuries.

No satisfactory explanation for the asymmetry or absence of the northern pair of smaller facing shrines has been advanced. Most Khmer monuments contain asymmetries and significantly none was ever completed; perhaps there was a taboo against humans aspiring to a god-like perfection, though there is no mention of one. On the other hand, interest may have waned with the death of the temple’s sponsor as undoubtedly happened elsewhere, for example, at Ta Keo, but human fecklessness seems too facile an explanation for such an obvious omission. A clue might be offered by a 12.5m shaft with a small cella at its base discovered under the north side of the sanctuary containing objects prescribed for a temple’s foundation in the Vastu Shastra. (In the wake of this discovery, similar shafts were discovered at Angkor Wat and the Bayon.) They may have their origins in the earliest cave shrines of Neolithic, telluric deities of whom Shiva Gambhiresvara might well be a syncretized version. Was there an inhibition against obstructing the influx of this literally “deep knowledge” from the auspicious northern direction associated with Shiva‘s Himalayan retreat? The northeast and northwest corner shrines face each other, like the six, smaller gateway aedicules on the east, west and south, but in contrast with their southeastern and southwestern counterparts, perhaps marking them as a wide gateway for the deity, the “Lord of the Three Worlds,” another of Shiva’s epithets, to enter his shrine. Like so many things at Angkor, Ak Yom, the first “temple mountain,” does not divulge its secrets but intrigues by what seems to be its builders’ deliberate but inscrutable intentions. The temple does reveal that, even in pre-Angkorian times, the Khmer had a preference for dispersing or projecting similar aedicules to define the boundaries of a temple’s enclosures rather than clustering miniature aedicules around its central shrine or shikhara as developed in India.

22