BANTEAY SREI

(967)

BANTEAY SREI

(967)

“TREE OF LIFE” PEDIMENT, BANTEAY SREI (967)

The temple's less-than-life-size scale and its remote location from the court at Angkor is usually attributed to the discretion of its donor, Yajnavaraha, a brahmin, ayurvedic doctor, Vedic scholar, personal guru and possibly eminence grise or "power-behind-the-throne" of Rajendravarman (944-968,) as well as, teacher of his son, Jayavarman V (968 - 1000.) His temple's modest dimensions may have been a deliberately circumspect, architectural under-statement of his real position and ambitions, lest he stir suspicions in the two monarchs he served, to say nothing of rival courtiers.

He thus averted the fate of a later and less prudent architectural patron, Nicholas Fouquet, the wealthy French noble whose opulent, path-breaking chateau, Vaux-le-Vicomte, so aroused the envy of Louis XIV, he had the over-weening official imprisoned for the rest of his life and then hired his architect, La Vau, landscape genius, Le Notre, and interior decorator, Le Brun, to burnish his own grandiose palace. Imitation may be the highest form of flattery but one doubts it was worth it to Fouquet who, nonetheless, had his revenge: while Vaux is regarded as a masterpiece, Versailles strikes many as a pompous bore.

Some of the enigmas of Banteay Srei may become clearer within the context of the unsettled, not to say viperous, Khmer court in which Yajnavaraha precariously maintained a key position. This brahmin's grandfather was Harshovarman I (915-923,) who like his ill-fated brother and successor, Isanavarman II, (923-928) were sons of Yashovarman I (889-915.) The brothers' succession was successfully, if dubiously, contested on behalf of the maternal line by Jayavarman IV (923-941) and his son Harshovarman II (941-944) who ruled from Koh Ker. Rajendravarman, (944-968,) most likely killed his uncle and cousin, Harshovarman II, to wrest power back to the paternal line of Yashovarman I (889-915) which claimed descent from the rulers of Chenla. He affirmed his legitimacy by returning the court to Angkor and finishing Baksei Chamkrong, the "ancestor temple" of Yashovarman I. Thus, Yajnavaraha, as the grandson and direct descendant of that king had a claim to the throne, at least as convincing as Rajendravarman but, as a political realist, may have preferred the tranquility of a scholar's life to that of a pretender.

Upon Rajendravarman's death and the ascent of his ten-year old son, Jayavarman V, Yajnavaraha, his tutor, as well as, other high court officials, served as regents for the young king. Since there are strikingly few records of any actions taken during Jayavarman V's long, 32- year reign but many references to his counselors, the government of the empire may have remained in the sticky hands of these mandarins. That monarch’s own state temple mountain, Ta Keo, was left unfinished at his death and the capital planned around it never begun. The role Banteay Srei may have played in the young king's life remains pure speculation but, given its sponsor's central role in its construction, the temple may have acted as home, boarding school and novitiate during that monarch's formative years. It is often observed that the temple's doors and ceiling are too low for adults to pass through without bowing – but not a ten-year old king; as an adult, Jayavarman V may have remained if not in his tutor's house, at least under his wing. There is no evidence for a royal residence during his reign, though Angkor Thom may have been begun at this time as a de facto administrative center. Upon the king's death at 42 around the turn of the millennium, the record shows his privy council of brahmins was decisive in finally resolving the disputed succession between the two rival emperors, Jayavirvarman (1002-1010) and Suryavarman I (1002-1049.)

Banteay Srei is undoubtedly the most photographed Khmer temple – at least per square meter – exceding even Angkor Wat. This catalog can add little to that visual plethora and so will restrict itself to a few general observation about the temple's structure, sometimes overlooked in appreciating this best-preserved Khmer shrine with the most crisply carved and dramatically engaging lintels, pediments and decorative scrollwork at Angkor. The temple has been compared to a "dolls' house" because of its diminutive proportions but it also shares the unreal – or hyper-real – sense of fantasy found in medieval miniatures and tapestries, of almost too-minutely observed details; indeed, its extensive repertory makes it a kind of illustrated story-book of the major Hindu myths. In this sense, Banteay Srei could be seen as an aedicule of a Khmer temple, a model like the rathas at Mamallapuram; if so, its innovations make it a simulacrum without an original.

SCROLLWORK SURROUNDS OR SHAKAS,

SOUTH LIBRARY, BANTEAY SREI (967)

A TEMPLE OF INNOVATIONS

Banteay Srei's site plan reveals that, despite its modest size and peripheral location, it introduces several innovations which would figure prominently in Angkorian temples' subsequent development. Some of these seem to have originated at Koh Ker, the ostentatious political and architectural "outlier" Yajnavaraha and Rajendravarman did so much to return to wilderness. They also suggest that the temple may not have been intended primarily as a rural retreat for the brahmin sage but for the king, who died the year of its completion and for his son, whose education was entrusted to its ostensible sponsor.

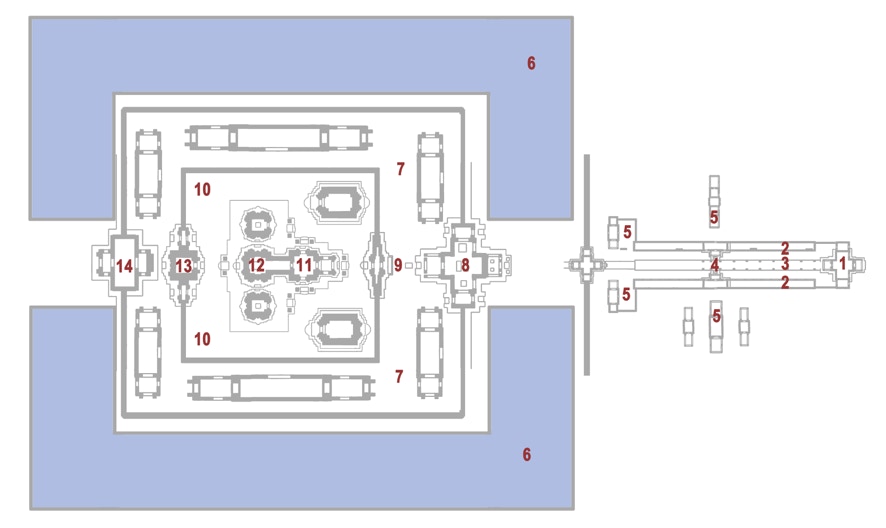

SITE PLAN, BANTEAY SREI (967)

KEY: SITE PLAN, BANTEAY SREI

1 – 4th east gopura

2 – Causeway, parallel colonnades

3 – Causeway, central processional corridor

4 – Causeway, medial gateway

5 – Service buildings, reception halls

6 – Moat

7 – 2nd enclosure

8 – 2nd east gopura

9 – 1st east gopura

10 – 1st enclosure

11 – Mandapa

12 – Central shrine, shikhara and antarala

13 – 1st west gopura

14 – 2nd west gopura

Banteay Srei’s atypical features include an "unenclosed" 4th enclosure like Koh Ker's, merely implied by its 4th east gopura (1,) perhaps the reason it is the largest in the complex. A long, wide causeway leads from there across marshy ground to the 3rd east gopura, lined on either side by covered colonnades (2,) like the shorter, narrower causeway across the moat between Koh Ker's 3rd and 2nd enclosures; causeways also cross the 4th enclosures at the Baphuon (1061) and Angkor Wat (1113-1150.) A corridor (3) lined with pillars or "boundary stones" runs down the causeway's center, like the markers along the causeways of the unwalled enclosures at the mountain temples, Preah Vihear (11th Century) and Phnom Rung (1113-1150.) These resemble sema around a Thai phra ubosot, a Buddhist "ordination hall,” which set it off as a sacred, though unenclosed, space. At Banteay Srei, they mark out a central "processional path" between the causeway's colonnades, suggesting it may have been reserved for a royal person or persons, while others were restricted to the sides aisles. Midway along the causeway, two medial pavilions (4) form a kind of gateway in roughly the same position as the cruciform terraces in front of Angkor Wat and the Baphuon. These pavilions give access to narrow "service buildings" (5) beside the causeway, analogous to the reception halls before Koh Ker's 4th east gopura, the courtyards of Preah Vihear's 3rd north gopura and the two Khleangs (c.1000) at Angkor Thom. These may have served as rest houses where distinguished visitors could be refreshed or robed for rituals in the two inner enclosures (7,10,) however, they lack the courtyards and space to lodge dignitaries found at the "palaces" at Koh Ker, Phimai and Phnom Rung, (perhaps unnecessary because of the temple's comparative proximity to Angkor Thom.) A wide moat (6) separates the implicit, outer 4th and 3rd enclosures from the inner 2nd (7) and 1st (10,) like the one found at Koh Ker, the two which once surrounded the Bakong, as well as, those around the 1st enclosure at Prasat Hin Muang Tam, the 4th enclosure at Angkor Wat, and the city walls of Angkor Thom. The narrow 2nd enclosure (7,) lined with "service buildings,” is similar to the ones at Koh Ker, East Mebon (953) and Pre Rup (961;).as there, the 2nd east cruciform gopura (8) has become almost fused with the 1st (9,) an architectural "enjambment" also found at Koh Ker and "linearly -expanded temples" such as Phnom Rung, Phimai, Beng Mealea, and in the crowded inner enclosures of Jayavarman VII's "temple monasteries," Ta Prohm (1186) and Preah Khan (1191.) The 2nd enclosure became increasingly vestigial over the course of Khmer history, another trend prefigured by this temple.

SOUTH FACE, MANDAPA, BANTEAY SREI (967)

A new or never so clearly articulated feature at Banteay Srei which would became a canonical part of most subsequent Khmer temples – except "temple mountains" – was the hall (11) in front of the square garbagriha or central shrine (12,) called in Sanskrit a mandapa or mantapa (Kh >. moudop; Thai > mondop.) This functioned as a place for worshippers to congregate and wait their turn for a glimpse of the auspicious darshan or sight of the awakened god, one purpose of Hindu puja or worship. At Banteay Srei, the mandapa takes the form of a discrete, square chamber with a nave and aisles with an unusually long, narrow vestibule or antarala, a uterus to the garbagriha or "womb chamber" to its west. On the east, an ardhamandapa or "half pavilion" links the mandapa to the eastern entrance porch. The cross-section of the mandapa's roof resembles the split gavaksha or tri-lobed panjara arch of a valabhi alpa vimana with eave and aedicular half-story; at the center of each side, a prominent dormer projects from its eave like a kudu or nasi, covered by a torana arch or garland with a floral tympanum. The antarala and ardhamandapa share a similar but lower barrel-vaulted shala roof. The mandapa was an element of the earliest Indian temples, for example, the Malegetti Shivalaya at Badami and Durga Temple at Aihole, both 7th Century, where it was an outgrowth (or “ingrowth”) of the open porch, mukhamandapa or face-mandapa; both gudhamandapas (enclosed) and rangamandapas (open) would grow in size and number in Indian temple architecture. Their sudden appearance in Cambodia at this late date may indicate direct contact with India at the time, although the Khmer never elaborated the mandapa beyond what is found at Banteay Srei. An analogous structure, a rectangular hall with eight columns, nave and aisles, connected to the central shrine can be found in the 1st enclosure at Koh Ker (928-944,) perhaps the 1st in Khmer architecture, and another link to that renegade complex, while another mandapa-like hall stands without a shrine in the 2nd enclosure of Preah Vihear (c.1000,) where it was home to one of Suryavarman I's boundary lingas. The mandapa would become a key component in the “linear expansion,” axial projection or lengthening, of most Hindu temples, as described and diagrammed in section III of the introduction, illustrated by the Khmer temple at Phimai in Thailand (c.1100,) as well as the Kandariya Mahadeva Temple at Khajuraho (c.1030.) It was to prove an integral link in the later trend towards a totally enclosed liturgical axis, largely realized at Beng Mealea (c.1150,) Preah Khan (1191,) Banteay Chhmar and the Bayon (all 1181-1220.) In the photo above, the deeply incised scrollwork of the pilasters and portal of the west-facing, southern "library" are just visible at the right.

WEST FACE. THE THREE PRASATS, BANTEAY SREI (967)

DVARAPALA, SOUTHEAST CORNER OF

THE CENTRAL SHRINE, BANTEAY SREI (967)

Banteay Srei's mandapa (11) shares a jagati (pitha, stereobate or plinth) with a typical Khmer row of three prasats (12,) so closely spaced it is difficult to squeeze between them. It is not a great stretch from this to a trikuta or “three-peaked” temple, joining three garbagrihas around a single mandapa, found at Hoysala temples such as the Lakshmi Narasimha, Nuggehalli, the Veera Narayana, Belavadi, and the Chennakeshava, Somanathapura, all in Karnataka. The Khmer, however, remained loyal to their ekakuta or single shrine prasat; in fact, they built no more temples with more than a single shrine at their center, preferring, instead, to "laterally and axially project" single and double porches, as well as, galleries and towers from that central shrine. This process of "cruciform" or "axial and lateral" expansion is illustrated in section XI of the introduction using the Baphuon as an example.

The mandapa's guardians are monkeys, allies of Rama and Lakshmana in the Ramayana, the only creatures who not only survived that epic but thrive to this day in many temples dedicated to its gods and heroes. They contrast with the lions and elephants at Rajendravarman's temples, East Mebon and Pre Rup, adding to the sense of Banteay Srei as a place of retreat into myth and animal fables from the real daily threats and intrigues of a militaristic, feudal society like the Khmer. The male dvarapala or door guardian (at right) is more an ephebe or young recruit than the battle-hardened veterans guarding most Khmer temples. This too would be in keeping with the fanciful and relaxed ethos of Banteay Srei as a rural refuge; it would also be appropriate for a temple where a young king was being educated. The temple's graceful, sometimes playful, aesthetic may be responsible for its modern sobriquet which means "the citadel of women."

THE PEDIMENTS

TILOTTAMA FROM THE MAHABHARATA,

PEDIMENT, BANTEAY SREI,

MUSEE GUIMET (967)

This is one pediment from Banteay Srei which won't be found among the thousands of photographs of the site because it is in the Musée Guimet in Paris. The French archaeologists of the EFEO were generally scrupulous by colonial standards about pillaging the treasure trove of Khmer remains in their Cambodian "protectorate," preferring to ship moldings rather than originals back to Paris, but it appears they could not resist absconding with this, one of the finest examples of carving at Banteay Srei. French intervention was not as unpopular here as in neighboring Vietnam. After the fall of Angkor, Cambodia became increasingly vulnerable to its more powerful neighbors Siam (now Thailand) and Vietnam, losing large portions of its territory, including Angkor. In 1863, the Cambodian king had no option but to ask that his country be placed under French protection to preserve what remained. In 1907, the French "convinced" the Thai to return two northeast province they had annexed in 1831 and which contained the majority of Khmer sites presently in Cambodia.

This tympanum depicts an incident from Book 1 of the Mahabharata with considerable fidelity to the text as it has come down to us. The gods desired to rid the world of two asuras or demons, Sunda and Upasunda, who were disrupting dharma or divine order on earth with their uncouth manners. Rather than intervene directly with overwhelming brute force, as was their wont, they preferred to have the malefactors do the dirty work themselves. They cleverly sent the beautiful nymph, Tilottama, "she of the charming eyebrows," knowing this would turn the unchivalrous brothers against each other. As intended, each demanded her as his wife and settled the matter by clubbing each other to death; at the tympanum's top two apsaras celebrate another victory for the gods. This pediment is an outstanding example of the "Banteay Srei style" of ornate, almost in-the-round, bas relief carving on sandstone, illustrating a single narrative scene clearly in hyper-real detail. It is surrounded by a double arch or torana, the lower ending with rearing, five-headed nagas, while the upper forms a garland of many-veined vertical leaves, which suggest to some, leaping flames.

KHANDAVAPRASTHA FOREST FROM

THE MAHABHARATA, EAST- FACING PEDIMENT,

NORTH LIBRARY, BANTEAY SREI (967)

GAJALAKSHMI, PEDIMENT, 1ST EAST GOPURA,

BANTEAY SREI (967)

This tympanum and torana (arch) blend figurative and decorative elements into a unified vision of the fecundity and prosperity associated with the goddess Lakshmi, Vishnu's consort, depicted here showered with lustral, purifying water by two elephants, while a fountain of foliage splashes behind her. She sits on a garland with four swags of foliage held, not by a kala, but her husband's "mount" or "vehicle," Garuda, whose feathered legs morph into the petals of a flower and stamen. Though these blossoms suggest disturbingly the hood of a naga or serpent, the half-bird, half-man hybrid’s traditional foe, he restrains it from assuming bestial form. This theme is also hinted at by the two leogryphs, hybrids with a human body and lion’s head, who ride the crests of the garland's inward-curling volutes and represent Vishnu's, fourth, fierce incarnation, Narasimha. The motif of gajalakshmi is symbolic of her consort, representing his creative, female aspect or emanation, through whom he tames, reabsorbs and integrates his destructive, feral energy into his god-like nature. In some versions of the myth, Vishnu must ask Shiva to kill his two bestial, avatars, Narasimha and Varaha, the boar, to regain wholeness with his human and divine aspects.

The view of the temple from the west (at right) is one few visitors take the time to see, since the west of Khmer temples tends to be anti-climactic once the shrine is reached. The collapsed, conjoint 1st (13) and 2nd (14) west gopuras are visible directly ahead with the torana of one their "service buildings" on the ground at right.

2ND AND 1ST ENCLOSURES FROM

THE WEST, BANTEAY SREI (967)

The east pediment of the north "library" is devoted to another episode from the Mahabharata, one of ever-popular tales of Krishna's carefree (Sans. > lila) youth among the gopis or milkmaids of Mathura. Indra had unleashed a deluge to extinguish a fire in the Khandavaprastha or Khandava Forest near present-day Delhi which had been set by Agni, the god of fire, to kill the naga, Takshaka, who had been terrorizing the local villagers. The king of the gods is shown at the top on his three-headed elephant "mount," Airavata, like Poseidon charging through the waves of water he had loosed, while a number of drowning celestials seem to beg him for mercy. The verticals lines beneath this sea have sometimes been understandably mistaken for rain. They are, in fact, the hail of arrows from the bows of Krishna and his brother, Balarama, in their chariots on the right and left, (both considered avatars of Vishnu,) so dense they stop the downpour from flooding the forest; terrified villagers and easily recognizable local wildlife are visible between them. The multi-headed serpent, Takshaka, at the center of the composition, has been driven back into his natural element, water, by Agni's fire but has somehow escaped the brothers' torrent of arrows, as have the terrified birds around him. In an alternative account, Arjuna, the Pandava hero, and Krishna, his councilor, are burning the forest themselves to clear it of the naga tribes, representing indigenous hill people, so it could be cleared for grazing by the pastoralist Aryans, a practice still common in the Amazon and contributing to global warming. Indra, as protector of the forest, launched a thunderbolt against Arjuna but he prevailed with Krishna's help against even the king of the Vedic gods.

53