PHNOM

KROM

(889-915)

PHNOM

KROM

(889-915)

VIEW OF THE TONLE SAP, PHNOM KROM (889-915)

Along with Phnom Bakheng, Yashovarman II built two smaller, identical temples on the only other hills on the Angkorian plain, Phnom Bok to the northeast towards Mt. Kulen and Phnom Krom, south of today's Siem Reap. Phnom Krom stands on top of a 150m high hill, 15 km south of Angkor Wat overlooking the Tonle Sap or "Great Lake." Its position there indicates the importance that body of water played in insuring the power and prosperity of the Khmer Empire and Cambodia's economy today. The Tonle Sap is a tributary of the Mekong River which joins it at Phnom Penh. When the Mekong becomes swollen by the Himalayan snow melt and summer monsoon it causes the Tonle Sap to reverse its flow, flooding much of central Cambodia as far as Siem Reap and Battambang. This floodplain or "lake" is filled with freshwater fish, which provided the Khmer diet with its primary source of protein; in addition, the alluvial soil and wetlands made two rice crops a year possible. This could support a much large population to deploy in non-subsistence activities such as warfare and temple architecture, allowing the Khmer to become the dominant state in Southeast Asia and builders of the unprecedentedly ambitious monuments visible at Angkor today. This (unretouched) photo shows the view at sunset which lures tourists and locals alike to make the strenuous climb to the temple each evening.

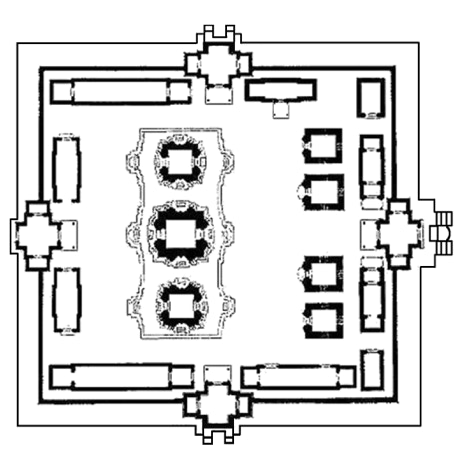

SITE PLAN, PHNOM KROM (889-915)

THE PRASATS FROM THE WEST, PHNOM KROM (889-915)

Phnom Krom and Phnom Bok share the same site plan, at least insofar as archaeologists have been able to reconstruct both badly depredated temples. They appear to have had one enclosure, necessarily restricted by their sites, with four identical gopuras in the cardinal directions. These enclosures were almost entirely lined by ten, narrow, three-chambered buildings of the type designated "service buildings" (in the absence of any knowledge of what that service may have been; suggestions have included hostels for pilgrims and wandering ascetics or storehouses.) They already were features at the Bakong (881) but were singularly lacking at the nearly contemporaneous Phnom Bakheng (907). Three east-facing prasats, or shrines were built upon a single north-south plinth, similar to the two rows of three already seen at Preah Ko and the three at Prasat Bei dating from the same reign. To the east of these shrines, i.e., in front of them since they are east-facing, four square west-facing buildings are hypothesized to have been crematoria, like the four proposed for the east of the Bakong's 1st enclosure. No evidence of vents or human ashes and bones, however, have been found at these or any other Angkorian site to conform these speculations; Khmer burial practices remain one of many mysteries. Perhaps the ashes were "scattered to the winds" from these aeries. At the same time these buildings are clearly differentiated from the shrines; they do not share a plinth or symmetry which, as seen at the Bakong and Phnom Bakheng, was an important element in differentiating the sacred from the profane.

Did the Khmer kings believe that the path to apotheosis and residence on Mt. Meru would be more expeditious if launched from the summit of a hill? They built at least three more "mountain temples" at Phnom Rung, Phnom Chisor and Preah Vihear. Religions are almost unanimous in associating mountains and divinity – not just across Southeast Asia, Indonesia and Mesoamerica, but at classical sites like Knossos on Crete, Delphi and Mt. Olympus on the Greek mainland, as well as, biblical peaks such as Mts. Sinai, Pisgah and Ararat. Though the Himalayas were the home of the Vedic Pantheon and proximate to the Indo-Aryan homeland, mountain temples (as opposed to "temple mountains") do not seem to have been common on the Indian subcontinent.

The three dilapidated prasats above, robbed of their pediments and lintels, their shikharas decapitated, held up by make-shift timbers, are unprepossessing, to say the least. They have steps up to their plinth on the west as well as portals rather than blind doors, even though like most Khmer shrines, they were east-facing with their ritual entrance on the opposite side. One can only speculate the Khmer enjoyed the view, as much then as their descendants do now. Two of the four, square, west-facing "crematoria" are visible in the background.

44